A groundbreaking genetic study has provided definitive proof of the North African Amazigh ancestry of the Segorbe Giant, a 1,000-year-old skeleton discovered in 1999 in an ancient Islamic cemetery near Segorbe, Spain. This finding aligns with previous DNA research on remains of Andalusian Muslims across southern France and Spain, all of which have been identified as carrying Amazigh genetic markers—with no traceable lineage to the Arabian Peninsula.

The genetic sequencing was conducted by an international research team led by the University of Huddersfield’s Archaeogenetics Research Group and published in Nature: Scientific Reports. The FTDNA Global Laboratory, a world-renowned genetic research institution, recently added the Segorbe Giant’s DNA profile to its list of Notable Connections after confirming that his paternal lineage belonged to the E-L19 haplogroup—the ancestral genetic branch of E-M81 and E-PF2431, both of which are widely recognized as Amazigh lineages.

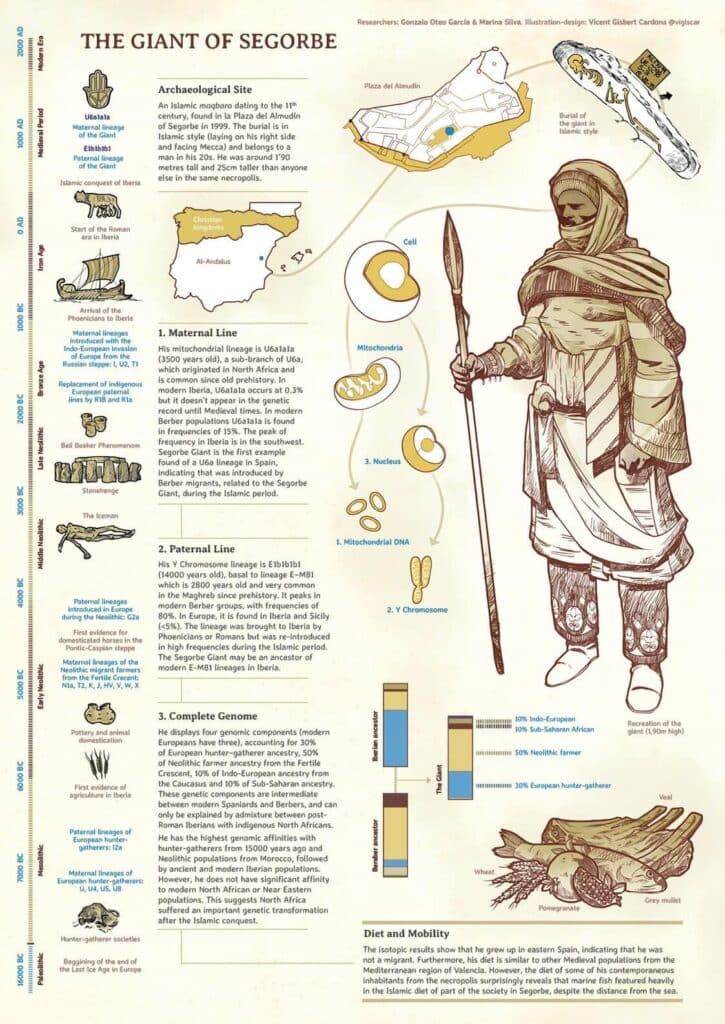

The Genetic Identity of the Segorbe Giant

The Segorbe Giant was a man in his twenties, standing at an extraordinary height of 190 cm (6’3”), significantly taller than others buried in the same cemetery. His remains were found in Plaza del Almudín in Segorbe, buried in accordance with Islamic customs, positioned on his right side facing Mecca.

The genetic analysis revealed that he inherited Amazigh DNA from both parents, yet more than half of his overall genetic makeup was Spanish. This suggests he lived in a culturally integrated Andalusian community where North African Muslim immigrants and local Spaniards coexisted and intermarried. Further isotope analysis confirmed that he was born and raised in eastern Spain, indicating his North African ancestors had settled there several generations earlier.

Interestingly, the study also found that his diet differed from that of his peers—he consumed more meat and grains rather than the seafood commonly eaten in this Mediterranean region. This could indicate either a privileged status or a distinct cultural dietary practice.

A Vanishing Legacy: The Expulsion of Andalusian Muslims

One of the most striking revelations was that the Segorbe Giant shares no genetic lineage with modern-day inhabitants of Valencia. This aligns with historical records documenting the tragic fate of Muslims in Spain. Following the Christian Reconquista, thousands of Muslims—including Moriscos (converted Moors)—were expelled or executed in the early 17th century. As a result, their once-thriving communities were erased, and their genetic legacy largely disappeared from the region.

The Segorbe Giant’s DNA serves as a powerful testament to the diverse and complex history of Al-Andalus, shedding light on the rich Amazigh heritage that once flourished in medieval Spain—only to be violently uprooted and lost over time.

This study further reinforces the broader genetic findings on Andalusian Muslim remains across southern France, Spain, and the Canary Islands, all of which have been scientifically proven to carry strong Amazigh genetic markers, particularly the E-L19 haplogroup, which remains prevalent today among Berber-speaking populations—especially in southern Morocco, where it reaches up to 98% frequency.

The Segorbe Giant is more than just an archaeological discovery—his remains tell a story of identity, migration, integration, and loss. His Amazigh heritage, now scientifically confirmed, adds yet another layer to our understanding of North African influence in Al-Andalus and the genetic legacy that was tragically erased from Spain’s history.