In the first two decades of the 1st century, a peculiar military leader named Tacfarinas asserted himself as a constant thorn in the side of the Roman Empire by unrelentingly threatening their interests in North Africa. Thankfully for us, the Roman historian and statesman, Tacitus (c. 56-117), kept fairly detailed records of Tacfarinas’ campaigns within his book, The Annals of Imperial Rome. Even though The Annals focused on the actions of the imperial family, especially Emperor Tiberius (r. 14-37), Tacfarinas’ name made numerous appearances in the pages, popping up each time he launched another invasion of Rome, which seemingly occurred every other year. So, even though Tacitus often sidelined describing Tacfarinas’ reign of terror in favor of discussing political maneuverings in Rome, a decent sketch of Tacfarinas’ life can be drawn from The Annals of Imperial Rome.

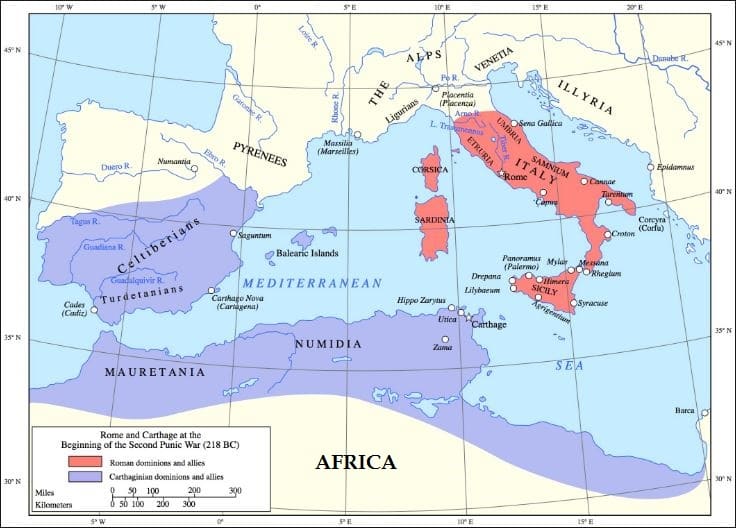

Tacfarinas was born in Numidia, and like many of Rome’s greatest threats, he began his career in the Roman military as an auxiliary soldier serving in North Africa. He eventually deserted from the Roman military and started a new life as a bandit. His ambitions, however, were too broad for common thievery. He gathered a large band of marauders and began to teach them Roman military discipline and tactics. Once he had gathered enough resources, he even equipped an elite core of his forces in Roman-styled weaponry and armor. Finally, Tacfarinas somehow maneuvered himself into becoming chief of the Musulamian tribe, a strong Numidian people known for their great warriors. With his newfound power, Tacfarinas was able to strike up a secret alliance between his own troops and other anti-Rome factions in North Africa. Along with Tacfarinas’ own bandits and Musulamian soldiers, the Cinithii tribe and dissidents from the Roman-aligned kingdoms of Mauretania and Garamantes also joined the growing coalition.

[ads1]

Around the year 17, Tacfarinas and his allies commenced their first major campaign against the Romans. Tacfarinas kept his elite core of disciplined, well-equipped troops encamped while his more disorderly allies raided the province. When the Roman governor of North Africa, Marcus Furius Camillus, marched out to halt the raids with only a single legion backed by auxiliary forces, Tacfarinas called together his troops and moved to meet the Romans. According to Tacitus, Tacfarinus started the battle with a clear numerical advantage over the Romans, yet, in the end, his small band of trained and equipped forces could not make up for the failings of the vast majority of the North African coalition. Camillus and his Roman legion won the battle and drove Tacfarinas back into the desert. When news reached Rome of the great victory, Emperor Tiberius threw a Triumphal parade in honor of the battle.

Despite suffering a major defeat, Tacfarinas had no intention of giving up his struggle against the Romans. Instead, he learned from his mistakes, rebuilt his forces and devoted more time to training his men and developing strategies to use against the Romans. Around the year 20, Tacfarinas finally led his revitalized forces out of the desert and resumed his war with Rome. He started slowly, beginning with quick raids and ambushes. Next, he began to pillage villages and loot small, under-defended settlements. Finally, with his confidence growing, Tacfarinas set out to test his luck against the Roman military. He managed to corner a Roman legion by the river Pagyda. He successfully encircled the legion and killed its commander, causing the soldiers to flee. It was such an embarrassing defeat that the new Roman governor, Lucius Apronius, decided to revive an archaic form of punishment—decimation. Every tenth Roman man who survived the battle was supposedly flogged to death.

Spurred on by his successes, Tacfarinas laid siege to the Roman fort of Mala. His men, however, had little experience in siege warfare and the fort’s garrison was able to successfully defend the position. Recognizing that sieges were not one of his strengths, Tacfarinas adjusted his strategy. He returned to guerilla warfare, focusing on persistent ambushes, looting and intimidation. Ironically, the success of his raiding parties would ultimately put an end to this particular campaign. Tacfarinas’ troops became so bogged down by loot that they were caught by the Romans near the coast, and after suffering a major defeat, were forced back to the safety of the desert.

Tacfarinas did not remain in hiding for long. By the year 21, he had already resumed his guerilla campaign against the Romans, and by the year 22, he felt strong enough to send a representative to Emperor Tiberius, offering peace for a grant of land. The emperor, however, had no intention of negotiating. Instead, he appointed the experienced military leader, Quintus Junius Blaesus, as the new governor of North Africa and ordered him to stop Tacfarinas, once and for all.

When Blaesus arrived in the province, he reworked the preexisting Roman military strategy to better tailor his troops against Tacfarinas’ guerilla warriors. He broke up his legions into small divisions and embedded them into a network of defensive forts throughout North Africa. At the same time, he organized new divisions of fast, mobile soldiers who were trained in desert combat. While the heavier, slower Roman soldiers defended the province in stationary forts, the quicker desert forces remained in constant pursuit of Tacfarinas. The Numidian leader did not know how to respond to this new defensive style, and found that he always had to keep constantly on the move to evade Blaesus’ fast-moving hunters. Eventually, Tacfarinas withdrew to the desert to reassess the situation, but not before his own brother was captured by the Romans.

Emperor Tiberius saw the decrease in Tacfarinas’ presence as a sign of victory and lavished great praise on Blaesus. Thinking that the dissidents in North Africa were pacified, Tiberius diverted one of the legions stationed in Africa to another region of the empire. Tacfarinas, who was still very much alive, saw this as a weakness he could exploit.

In the year 24, after the legion had left North Africa and Blaesus had been replaced as governor by Publius Cornelius Dolabella, Tacfarinas led his coalition in another war against Rome. Tacfarinas was feeling confident, so he decided to attempt another siege. This time, however, his target was not a fortress. Now, he wanted to take the city of Thubuscum. When he heard of the siege, Governor Dolabella gathered the remaining troops in the province and marched to relieve the city. Seeing the governor’s approaching forces, Tacfarinas remembered his earlier defeat at the hands of Governor Camillus’ small army. Fearing a similar situation, he decided to end his siege, flee and then wait for a better time to engage the Romans.

Governor Dolabella, using a tactic of his predecessor, Blaesus, mobilized four columns of lightly-armored, quick-moving auxiliary and allied troops that were tasked with chasing down Tacfarinas. Working in tandem with the larger columns were also numerous small squads sent to scour the province for information and punish sympathizers. Eventually, word reached the Romans that most of Tacfarinas’ troops were camped at a damaged fort in Auzea. Dolabella immediately sent his quickest infantry and cavalry to intercept the enemy at the fort before they could slip away. Amazingly, the Romans caught Tacfarinas’ forces by surprise and took the fort without much trouble, capturing or killing all who had been inside. Yet, Tacfarinas escaped, or had never been at the fort, in the first place. Nevertheless, with the defeat at Auzea, the North African coalition seemingly lost all confidence in their leader. According to Tacitus, Tacfarinas’ own bodyguards betrayed their leader to the Romans. The Numidian chief’s son was captured by the Romans, but Tacfarinas, himself, died while resisting arrest.

Written by C. Keith Hansley for The Historian’s Hut Articles.