Amazigh people across North Africa marked the anniversary of the death of now-revered Moroccan singer-songwriter Nba on January 9, 2011 nine years ago. Who was he and why was he once controversial and now celebrated across North Africa?

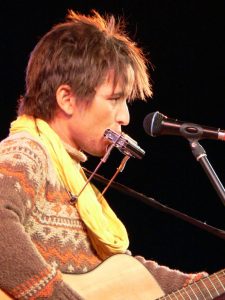

January 9 marked the ninth anniversary of the death of popular Moroccan singer-songwriter Nba Saghru. Born M’bark Oularbi, on September 9, 1982 in Mellab, a small village in southeast Morocco, Nba was the leader and founder of the Saghru Band.

Nba had discovered a passion for the arts at a young age. Influenced by Algerian Kabyle artists such as Idir, Oulahlou, and Lounes Matoub, he began to compose his first songs as a teenager. He sang with friends in high school and for events put on by cultural associations.

Along with his passion for music, he also valued education. At university, he joined the Amazigh Cultural Movement (MCA) and founded the Saghru Band. By 2006, the band was becoming well known for its driving rhythms and engaging protest lyrics. Its songs addressed social and political issues, especially the notion of reclaiming Amazigh cultural identity.

Along with his passion for music, he also valued education. At university, he joined the Amazigh Cultural Movement (MCA) and founded the Saghru Band. By 2006, the band was becoming well known for its driving rhythms and engaging protest lyrics. Its songs addressed social and political issues, especially the notion of reclaiming Amazigh cultural identity.

Nba received a degree in law from the University of Meknes and another in French literature from Errachidia. By this time, Nba had become well known all across North Africa for songs celebrating Amazigh culture and history and protesting the marginalization of Imazighen (the Amazigh people). Songs such as Muha, Grad ifassen, Ulac smaḥ ulac, awes-i i tala, and tabrat i Ubama earned him wide acclaim.

As an outspoken activist and musician, he became “the conscience of the people.” But there were also detractors who strongly criticized him for not being militant enough and for supposedly capitulating with apologists for the Amazigh struggle.

[ads1]

Not only a singer, but also a guitarist and flautist, he expressed what was on his mind—with no holds barred. As an outspoken activist and musician, he became “the conscience of the people.” But there were also detractors who strongly criticized him for not being militant enough and for supposedly capitulating with apologists for the Amazigh struggle. Nba, in his songs, however, overtly criticized both le Pouvoir (the government) in Algeria and officials in Morocco who pretended to fight colonialism by the French but who in reality negotiated in their self-interest.

Nba released the albums “Muha,” “Tillili” (Liberty), and “Message to Obama” in 2007, 2008, and 2009, respectively, giving birth to a new style of Amazigh song called Amun. Unlike more traditional Amazigh styles of Arabic music where the melody line is sung in unison, Amun uses polyphony and harmony woven around a main voice, and punctuated by rhythms that are purely native Amazigh specific to the music of the southeast region.

In addition to traditional instruments like lotar, Amun features modern instruments, especially the violin, the banjo, and the guitar, and of course percussion. Other instruments such as ghita, flute, harmonica, trumpet, clarinet, trombone, and tuba, and later saxophone, were added.

In addition to traditional instruments like lotar, Amun features modern instruments, especially the violin, the banjo, and the guitar, and of course percussion. Other instruments such as ghita, flute, harmonica, trumpet, clarinet, trombone, and tuba, and later saxophone, were added.

The songs on Nba’s first album “Muha” describe the life of Muha, who symbolizes both a poor man from southeast Morocco and a man from the broader North Africa. The lyrics evoke a break with colonialism, the loss of control of the life of a Berber confronted with the discovery of his undesirable identity, his unbearable continuity, and his systemic marginalization. The song speaks of betrayal, the current state of the Amazigh, a great disruption, and then reunion and the hope of a new life.

Brahim Ainani, a militant activist researcher in Amazigh culture and a close friend of Nba, told Inside Arabia, “As an Amazigh activist, I frequently quote the lyrics of our rebellious, blue-eyed singer from the southeast of Morocco.”

“In my country, die those who don’t deserve death . . . eradicated by those who don’t deserve life.”

He highlighted a few: “To exist is to revolt;” “Our cry is drying up, like a herb strangled to death by a weed;” and perhaps most strikingly, “In my country, die those who don’t deserve death . . . , eradicated by those who don’t deserve life.”

[ads1]

In 2004, Ainani was teaching English at Boumalne High School during a remembrance celebration of “the Amazigh Spring” of April 20, 1980 (Tafsout n Imazighn) attended by Nba. He says he remembers how Nba reacted to a question posed by students: “To whom should we pray!?”

Nba suggested Algerian Kabyle singer-songwriter and martyr, Lounes Matoub. “‘No one else deserves our prayers and tears but our prophet Lounes Matoub,’” Nba said, as Ainani recalls. “I think that was the main reason why, for the first time in the history of the southeast of Morocco, Arab fundamentalists issued a fatwa [in 2005] calling for Nba to be burned alive,” said Ainani.

“I think that was the main reason why, for the first time in the history of the southeast of Morocco, Arab fundamentalists issued a fatwa [in 2005] calling for Nba to be burned alive.”

Nba died in his hometown of Mellab at only age 28 on January 9, 2011, under mysterious circumstances. The cause of death remains a mystery. Many Amazigh believe Nba was poisoned. The official account, however, was that he died from Churg-Strauss syndrome, a disease characterized by asthma and other respiratory problems.

Only a few people, his family and a few acquaintances from his village, and friends from nearby towns, attended his funeral the next day. After news of his death spread over the next few days, a few militant intellectual activists, school children, and others started coming to visit his family and pay their respects at his grave.

Since his death, however, he has become an icon not only for other artists but also for young people. Many compare him to Matoub who also died under suspicious circumstances (many suspect assassination). Today, the cemetery in which Nba’s grave lies is a place of pilgrimage.

Nba’s brother Sliman Oulaarbi who had looked after Nba since he took his first baby steps, recalled him as a “brother, friend, friend of all,” as well as a “well-educated and high-level artist.” He credits Nba with elevating the Amazigh cause.

“Nba devoted his life to defending Timuzgha [Amazigh] values and in effect produced a revolution in Amazigh song.”

“His death is indeed a loss for the Amazigh people, for the Tamazight language, for Morocco’s south east, and in fact for any marginalized person,” Sliman said. “Nba devoted his life to defending Timuzgha [Amazigh] values and in effect produced a revolution in Amazigh song.”

“Thanks to him,” he continued, “many young people have embraced the modern music of militancy.” Nba’s ideas influenced thought among Amazigh youth both before and after the democratic spring in Morocco and North Africa, according to Sliman.

Nba received recognition by Morocco’s Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture the year before he died when he was awarded a prize for best Amazigh singer in 2010.

Note: Omar Zanifi served as the manager/promoter of the Saghru Band before Nba’s death.

This article was originally published on InsideArabia.com

[ads2]