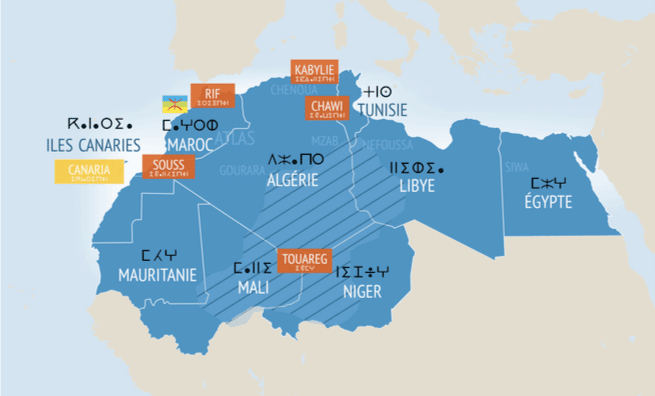

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hen we speak about Tamazgha, we always say that its territory extends from Siwa in Egypt to the Canary Islands. But to me, Siwa has always been a myth, a mystery because it is remote and of difficult access. Moreover, there is practically no literature on Siwa except some articles on its ancient history. And then, I had never met anybody who visited it and who can really speak about it. This convinced me that, in reality, Siwa is only a mirage which, comes to feed this dream of greatness among the Amazigh people in particular, but which also characterizes all people of the past. I then was convinced that the only way to satisfy myself would be to go and visit it.

I left with a friend, Said, without any information, to the adventure like one says. Right at the start, we noticed that even in Egypt (Cairo, Alexandria), people did not know anything about Siwa. Some people told us that it was an oasis like any other. Others told us that if we wanted to visit Egypt there are much more beautiful oases. As for the linguistic characteristic of Siwa, some thought that this language was derived from the Egyptian Arabic, and for others it was simply Egyptian Arabic but pronounced with a particular accent.

[ads1]

The trip was long (approximately 900 km of desert) but much less painful than we thought, except for the haste, to finally discover the legend, which, made us forget everything. The bus (the most practical means of transportation) stops very often because of the frequent military check points due to Islamist activism. From faraway, as soon as a small island of greenery appears in the middle of the Saharan ocean, we were taken by this feeling of relief and intense joy, which marks reunions. The oasis appears so small to us, planted in the middle of the immense Libyc desert. Wherever one comes from, it is necessary to travel hundreds of kilometers, of sometimes-rocky desert, sometimes sandy, which form infinite undulating dunes. More closely, Siwa proves to be finally a large oasis that is approximately 30 km long and 20 km wide, surrounded by two large lagoons that give it a fairy-like air.

With the arrival of the bus, there is always a small assembly of people who wait for mail, newspapers, medicine, tourists, etc. As we got off the bus, a teenager approached us, and in English proposed his assistance to carry our luggage to the hotel. My friend answered him spontaneously in Tamazight. The young man opened large eyes, moved back and screamed to the others: “ssawalen tasiwit! ssawalen tasiwit!” (they speak Siwi!) as if he had just discovered his life! All the inhabitants of Siwa accepted us as of this moment. They were extremely happy (so were we) to see, show, discuss, and touch as if to check that these moments were real.

[ads1]

We met an incalculable number people of every age, from the five-year old child to the old man, and of all conditions (let us say immediately that the social differences are hardly visible in Siwa). Everywhere the Siwis showed the joy of exchanging ideas, to tell their history as they know it, to talk about their daily life, and especially to ask many questions about the situation of the other Amazigh areas. These questions related to the way of life, the history of the Amazigh people, the language, the writing… Their welcome was such that our stay in Siwa was not long enough to be

able to accept all the invitations.

The Thirst for Knowledge

All Siwis have an immense thirst to know because what they know is not written and with the passing of time, the memory of Siwa was gradually erased. Whether it was the school principal, the post office staff, the farmer, the blacksmith, the person in charge for the “museum”, a group of musicians… Every morning people waited for us because they wanted us to talk to them in Tamazight, to learn from us and to help us discover their civilization and cultural heritage. It should be said that Siwa was completely closed to foreigners until the early nineties, and that electricity made its first appearance only in 1985.

In addition, the Egyptian medias were not especially oriented towards the rest of North Africa. Siwa was thus deprived of information about the rest of the Amazigh community. Practically, Siwa lived as a closed community. All Siwis (approximately 20,000) speak Tasiwit (Tamazight of Siwa), which they use in their daily life. They use Arabic or English only with foreigners. Tasiwit has resemblances with Tachelhit or Tachawit. Approximately 40% of the words used are loans from the dialectal Egyptian. That being said, at the end of one week, any Amazighophone of any area from the rest of North Africa will be able to communicate very easily in Siwi. Siwis do not know the written form, Tifinagh, nor the use of the Latin characters. On many occasions, at people’s requests, we had to write the Tifinagh alphabet, which seemed of a particular interest to them.

[ads1]

Here are some examples of words in tasiwit: aman (water), aksum (meat), agben (house), akkubi (boy), tle`a (girl), talt (woman), teltawin (women), netta (lui), azemmur (olives), tini (dates), maci (yes), ula1 (not), betin (which or what?), cek1 (you), tanta l;al nekk@ (how you are?), siwel didi (speaks with me), melmi (when), melmi g azrap cek@ (when will I see you?), zewel-as (greet him/her), isn’t from this that the word azul comes?

On the socio-economic level, the standard of living in Siwa is extremely low, even lower than the Egyptian average. A regular meal costs you the equivalent of 6 French Francs. There are many children who are working instead of going to school due to the extreme poverty. Siwis live almost in autarky of the date palm agriculture, the olive-tree and produce farming. It does not rain much but water is very abundant. There are many wells, springs and hot water fountains used for all kinds of purposes, possibly after its cooling in the air. Siwa produces and markets all over Egypt a bottled natural mineral water that bears its name.

Very Rigid Customs

Siwa is the only place in Egypt where one can eat a couscous (seksu)# It is prepared in the exact same way as in other regions of North Africa, with vegetables and chicken or lamb meat. This provides me with another proof that this famous dish is typically Amazigh. The Siwis are practicing Muslims and the density of mosques per inhabitant is extremely high. The customs are very rigid, noticeably when it comes to women, who are very rare in the streets and fields, and they are always entirely covered in black. When we pass by them, they turn their gaze away and pass furtively. In public places such as stores and cafes, there is no music. But the Islamic sermons on Taiwanese tapes are loudly diffused during the day. This shows the influence and hold of the Islamic Brotherhood on the Siwi society. There are however some places of free expression for men (I do not know if there are similar places for women). Like in most oases, there is this alcoholic beverage called lagbi (from the palm tree), which is freely produced. It is consumed during parties or between friends. Another curiosity is that the Siwis never go to cafes reserved to passing foreigners. They get together in some sort of neighborhood lounges to talk, listen to music, sing, dance, watch television, etc.

Siwa: A Virgin Space

For the tourist, Siwa is full of curiosities and historical sites: the beautiful remains of two Siwi typical ancient villages: Shali in the north of the oasis and Aghoumi in the south, the temple of Amon (according to the Siwis, this is the root of the word aman (water in Tamazight: common to all Amazighs), Adrar n lmuta (the mountain of death), a mountain that houses tombs from 664 B.C., many springs and hot ponds including the one used by the Amazigh king Juba II and that still carries his name. There is also the house of Siwa, which is a museum for local craft such as pottery, various utensils made of palm leaves, traditional clothes and some traces of the long history of Siwa.

[ads1]

For researchers, Siwa is still an un-explored field in the domains of economy, sociology, linguistic, ethnology, history… that needs to be cleared, but with extreme care. Closed to the outside world for a long time, and having known only the desert and the Egyptian television (another desert that is sadder than the real desert), the Siwis, young and not so young, aspire to exchange ideas with the outside world especially with their brethren from other regions of Tamazgha. There are many more things to tell about Siwa but the following anecdote will give you an idea on the state of thought in Siwa. Youssef is a young artist who was asked by the municipality of Siwa to design a monument to be built in the central place of Siwa. He showed me his project, already designed, which represents some symbols of Siwa (springs, palm orchard, Shali, etc.). He told me that since our meeting, he decided to modify his project by adding the Amazigh symbol ⵣ (Z in Tiffinagh).