By Mohamed Chafik,

Translated from French by Rabah Seffal.

Many Arab and European historians held a sharp curiosity about the origins of Imazighen. During the middle Ages, Arab genealogists convinced themselves with acrobatic demonstrations that Imazighen were Arabs and that they had immigrated to North Africa a long time ago. This opinion continues to be the only one allowed in the Arab world today. Upon their invasion of Algeria, the French in their turn were able to convince themselves that the Numids, the Moors and other Berbers, were of GalloRoman, Celtic, or straightforwardly Scandinavian origin However, it seems that the genetics now had settled the question: the oldest recognizable cradle of Berber civilization, in the current state of science, was the Central Saharan desert when it had a lot of water and covered with vegetations. The merit belongs to a team of mostly Spanish geneticists and archaeologists who published a book in English entitled “Prehistoric Iberia, Genetics, Anthropology, and Linguistics” in New York in 2000.

Imazighen were not only the neighbors of the Egyptians but also their cousins. A similar assumption, which started after the examination of some elements of Amazigh lexicography, was mentioned in my talk at the Academy of the Kingdom of Morocco on June 6th, 1995. An ensuing article was published in French in the Moroccan journal “Tifinagh” in the double volume 11 & 12 of August 1997. One question to ask is: “How is it that the Egyptians quickly and completely became arabicized whereas Imazighen still cling to their identity?” In addition, what constitutes the specificities of this identity? The answer is the geographical factor.

In the seventh century, Egypt yielded to the Arab invasion within few months while the rest of NorthAfrica resisted an entire century, from 640 to 741, and was able to obliterate the military power of the invader. This contrasts with the French historian Gabriel Camps’ peremptorily affirmation that Imazighen “never could stand up to the invaders”.” Did he mean that they failed to withstand the attackers’ first strikes? However, two other researchers, Charles-André Julien and D. Rivet, who researched the earlier period of times, expressed a different opinion. Julien (p. 194) wrote, “If Roman civilization seemingly conquered the lowland cities, it did not touch the mountainous regions… ” and “came the time when the Roman forces fell apart. That was when the Romanization proved to be superficial and limited.”

The Belgian historian, Marguerite Rachet, reminding us of the geography, drew the following conclusion: “Rome dreamed to dominate agricultural and thriving Tamazgha… This ambition assumed a total upheaval of the social practices of the natives, which were generally founded on the semi-nomadic traditions.” As for D. Rivet, who spoke about the French pacifying Morocco at the beginning of the 20th Century in a chapter entitled “A thirty-year Old War”, he did not hesitate to write, “resistance was primarily from the Amazigh mountain dwellers. This confirms the postulate that Imazighen initially define themselves by their eternal insubordination to the central power, when it is foreign, and by an in -depth irreducibility….”. Camps himself reconsidered his opinion and celebrated, therefore, Imazighen when he wrote, ”these proud people, however, have always expressed a hard core and vibrating identity and a strict idea of honor.” This in-depth irreducibility has its bedrock in the nature of the terrain and the military and political organizations, which resulted from them.

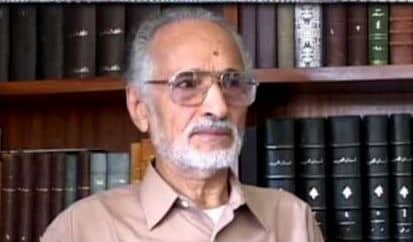

About the Author:

Mohamed Chafik is a leading figure in the Amazigh cultural movement. An original author of the Amazigh Manifesto, he was later appointed as the first Rector of the Royal Institute of the Amazigh Culture. He has worked extensively on incorporating Amazigh culture into Moroccan identity and is a leading intellectual of the Moroccan intelligentsia.