[dropcap]A[/dropcap] magnificent stream of people pours down a long street in Boston; an intermingling of signs, screams and emotions, all crying for justice for the recently deceased George Floyd. “Black Lives Matter”, “Justice for George”, say some signs. “End Police Brutality” demand others. But among the unending currents of signs and people, a peculiar sight: a group of black Americans holding the Moroccan flag, some of them wearing the famous Moroccan red hat, the Fez, with signs and t-shirts proclaiming “We are not black, we are Moors!”, and “Moors are Moroccans!”. To the unsuspecting Moroccan, this may look like another group of Moroccan migrants, or descendants thereof, expressing their attachment to their ancestral origins. But there is more here than meets the eye.

[ads1]

Who are the Moors?

“The Moors” is the name Iberians gave to the Muslim Berbers and Arabs (Arabs being a minority according to many historians, among them Stanley Lane-Poole, as well as modern genetic studies) who conquered the Iberian Peninsula in 711 AD, and ruled it for nearly 800 years. But Iberians did not invent this name. It has a much much older history, and most likely shares a root with the name of our country “Morocco”.

Why all the fuss about their skin colour?

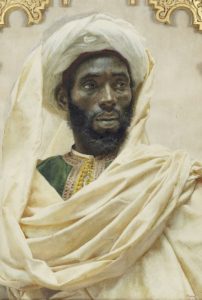

Recently, debates arose about the Moors and their skin colour. A myriad of articles and YouTube videos about them might have popped up in your feed, claiming that the Moors, civilization builders in North Africa and Andalusia, were originally black. Some go as far as to claim that today’s Moroccans are only recent invaders, who “expelled the real Moor”. But far from being factual, the only arguments these articles and videos have to back up their premise, of the Moors being dark-skinned Sub-Saharan Africans, is a couple of relatively recent paintings of black Moroccans from the 18th and 19th century, and a fallacious etymology of the word “Moor” (they allege that it means “black”).

[ads1]

It is true that the Moors were Africans, and there were times in history when the terms “African”, “Moor”, and “Berber/Amazigh” were interchangeable; but claiming that they were dark-skinned or Sub-Saharans is nothing but an ideologically motivated lie, with little substance and without any consideration to the history of a whole people, us Moroccans.

We Moroccans are familiar with the story of the Islamic invasion of Spain. We know about Tarik Ibn Ziyad and his army of Amazighs, and about the Almohads and the Almoravids. But we never refer to them as Moors. The latter is what the Iberians called them (Los Moros). They would much later call us “Moroccans”. The fact that the Iberians referred to both the invaders of Iberia and North-West Africans with the same term, is sufficient proof that they were perceived as one and the same people.

[ads1]

Where did the name “Moor” come from?

The Greek geographer and historian Strabo talked about the Amazigh population of the ancient kingdom of Mauretania (present-day north Morocco and north-west Algeria) and wrote that their native name was Mauri, or Maurusii (Μαυρούσιοι) in Greek. Anyone who has any acquaintance with the Amazigh language will instantly think of similar words that might be etymologically related: Amur: Share, Tamurt: Land, Anamur: Citizen. Therefore, it does not mean “black” as those articles and videos allege. In fact, one can notice it in the name of the city of Marrakech (Amur (n) Akuch in Tamazight, meaning the land of God), the latter was the capital of the Almohads and Almoravids. And probably this is where Morocco, Maroc, Marruecos came from.

Moor meaning Moroccan

Morocco is famed for its unique history and rich culture. Numerable dynasties ruled the country, and established empires that controlled great parts of North Africa. These dynasties were referred to as “the Moors” and their empires and cultures as “Moorish”. As recently as the late 19th and early 20th century, the daily spoken dialect of Moroccans in urban centres, now known as “Moroccan Arabic” or “Moroccan Darija”, was called “Moorish Arabic” in the linguistic literature. This name was used until recently when the term “Moroccan” took its place, particularly under the French and Spanish protectorate and after independence.

[ads1]

In addition to the myriads of books that talked about Morocco (“Morocco that was” by Walter Burton, written in 1921, for example), one can take a look at the Moroccan–American Treaty of Friendship that was signed in 1786, and find out that the name Moor was used to refer to Moroccans. Therefore, when a painting from the 18th and 19th century portrays a dark-skinned Moor, it just means a dark-skinned Moroccan. The existence of dark-skinned Moroccans throughout history is uncontested. Their population grew significantly especially after Moulay Ismail’s reign (The fifth Alawite sultan), but in the grand scheme of things, it has always remained a small minority.

Thus, the claims made by some black American activists that they represented the descendants of “real Moors”, or that the Moors were black, are simply unfounded. Like many conspiracy theories, a good dose of historical and scientific knowledge is sufficient to dispel them, but if left unchecked, they can be dangerous and do a lot of damage. Sure, Moors are Moroccans, but they are none other than present day Moroccans in Morocco, pure and simple.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Amazigh World News’ editorial views.