Mano Dayak, internationally renowned Tuareg leader, was killed in a plane crash in the Adrar Chirouet region northeast of the Air Mountains in Niger, Saharan West Africa, on Friday, December 15, 1995.

Mano led the Tumast Culture) Liberation Front (FLT), one coalition among the various Tuareg resistance groups currently combined under the recently reformed Coordinated Armed resistance (CRA). In April 1995 Mano’s coalition had refused to agree to a Peace Accord with the government of Niger that was signed by another Tuareg coalition, the Organization of Armed Resistance (ORA). Mano’s allies remained opposed to the Peace Accord and continued to maintain their base of resistance in the Tenere Desert east of Agadez.

Mano, born in a nomadic setting and raised at Tidene, a home well area(2) in the south-central Air Mountains, received a diploma from the public high school in Agadez. He befriended some of the first American Peace Corps volunteers teaching English there in the 1960s and 1970s, as well as most of the European and American missionaries and representatives of non-governmental organizations working in northern Niger. He worked for a time with the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in Niamey, and was well-known among the American community in Niger. As a young man, Mano traveled to the United States, stayed with some of his Peace Corps friends, enrolled in an undergraduate degree program in folklore at Indiana University, and learned to speak near-perfect American English with a Midwest accent. He was keenly interested in anthropology and visited New York to talk with Margaret Mead about the Ph.D. program at Columbia, but later decided to pursue a degree in political science at the Sorbonne.

It was in Paris at the Sorbonne where he met and later married his wife Odile, an anthropology student who came with him to Agadez to help him establish a tourist business in the early 1970s. Several years later they had two sons. Mano and Odile’s tourist agency, Temet Voyages, began with two Land Rovers and several dedicated family workers, taking Europeans and Americans on trips through the vast Tenere Desert and the rugged Air Mountains, stopping to meet Twareg families and sample homemade food. Mano loved to introduce foreigners to his people and teach them about Tuareg culture. By the mid-1980s, Mano’s tourist business was a thriving success, and he had two dozen or more Range Rovers at his disposal, provided employment to scores of Nigeriens, and not only brought in a significant amount of business for hotels, restaurants, and merchants in the north, but also contributed substantially to Niger’s gross domestic product. Temet Voyages, partly because it was so efficiently organized by Odile and Mano, and partly because of Mano’s easy-going, friendly and gregarious personality, was frequented by thousands of tourists from many countries, a number of whom were wealthy and politically influential.

When I met him in 1976, Mano continued to pursue his interest in promoting Tuareg history and culture, and he and Odile were collecting a library of scholarly books, articles, and archival data on the Twareg people. One of Mano’s passions was to make a film showing Tuareg life-ways; another was to write a book about his people. Both his dreams came to fruition later in his life. Mano coordinated all the arrangements for the Saharan portions of “The Sheltering Sky,” a 1990 Hollywood film based on Paul Bowles’ novel, starring Debra Winger. Although a couple of the cultural details of the Agadez portion were somewhat compromised by the European tastes of the film’s Italian director, the film is the first to bring to American viewers the faces and voices of actual Twareg people, many of them Mano’s family and friends, as well as the cultural complexity and exotic beauty of life in Agadez, the remote and historic capital city of northwestern Niger. In his book “Tuareg, la Tragedie,” published in 1992, Mano put some of his deepest feelings into writing when he described the warmth and strength of his childhood upbringing and family, the effects of the colonial legacy on him personally and on the Tuaregs as a whole, the cruelties imposed by European history and the victimization of the Tuareg people as a result of it, the special meaning that Tuareg “Tumast” has had for him, and his hope of helping salvage it for the Tuareg people. Finally, in a Geo made-for-television film about Tuareg resistance, “Desert Prince,” that appeared in 1994, Mano was the central figure who discussed in detail some of the problems faced by his people and the reasons why he and his followers had decided to fight the overwhelming injustices and atrocities imposed upon the Tuareg population.

Those who remember Mano personally will remember his charismatic personality, his easy way with humor, his intelligence and wit, and his undeniable leadership skills. Mano was as comfortable in the most humble settings as in the most aristocratic. He could mount a camel as easily as engage in clever repartee at a cocktail party. He was a magnet for people, and had thousands of friends and admirers. Mano was helpful and generous to many. He had a strong vision of hope for the Tuareg people and a brave heart to pursue his goal patiently. Not everyone agreed with his politics, but he remained to the end eclectic and romantic, dead set to stand his ground and fight for what he considered the true path, for a solution that was visible and tangible, not just in writing. As the husband of a French citizen, Mano could have given up the struggle and retired safely to France, but he chose what he believed was the nobler path, the destiny of a warrior poet.

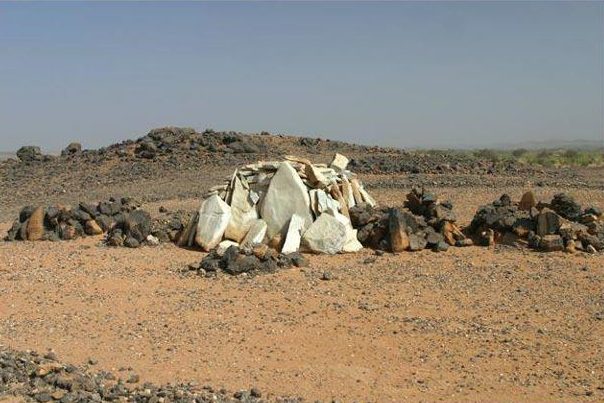

Mano was killed on his way to peace talks with the Nigerien Prime Minister in Niamey, along with two Twaregs, a non-Twareg Nigerien pilot, and a French journalist, in a Cessna 337 that crashed shortly after take-off east of the remote Air Mountains north of Agadez. The catastrophe is still believed by some Twaregs and others to have been a result of sabotage, even though an international team of investigators visited the crash site and declared it to be an accident. Some sources say the airplane’s wing may have struck a tree or rock during take-off in the desert. Mano’s violent death is a tragedy that has inflicted a deep wound in the peace process. Mano was fluent in French and English; he was well-educated and highly knowledgeable about international relations and technology. Mano was in a uniquely significant position to evaluate and defend the Tuareg people’s rights.

Just before Mano’s death, according to one source, the Nigerien government had terminated the April 1995 Peace Accord because it felt that Tuaregs were “not maintaining security in the north.” Tuareg sources say that the north has been unstable in the wake of both peace agreements, and that Tuareg civilians have sporadically been attacked by either Nigerien soldiers or military-supported Arab militia members.

The brutality of Mano’s own death, believed by some to have been instigated by either France or Niger because Mano was holding out for protection and better treatment of the Tuareg people, forces us to consider the reasons why Mano and other Tuaregs chose to oppose the Peace Accord. Many Tuaregs were unsatisfied with the April Peace Accord because neither the previous Peace Pact which Mano signed in October 1994, nor the Peace Accord signed by the ORA in April 1995 had resulted in any improvements for Tuareg civilians living within Niger’s boundaries, particularly in terms of security against retaliatory attacks by the Nigerien military and Arab militias allegedly supported by the military, as well as practical and sorely needed reforms in democratic governance, more equitable Tuareg representation in government posts and the national military, and equal health care and education for rural people in the north of Niger, which is inhabited largely by Tuareg people. Mano, along with many other Tuaregs, had observed that, in spite of the Accords, sporadic retaliatory acts of violence continue to be committed on innocent citizens by agents of the Nigerien army. Mano also decried the fact that, in spite of what the Accords prescribed, nothing has been done economically or politically to empower and rehabilitate Tuareg populations in the north, weakened and marginalized by decades of political neglect and economic deprivation (discussed in his book).

The “Tuareg problem” as reported in the Western press has often been described as an “ethnic conflict,” but some Nigerien government officials, as well as some Tuaregs, say that, although there is a historic basis for ethnic hostility, the roots of the current violence are essentially economic. Other Tuareg say that the way their people have been treated -as a population- could only be explained in terms of ethnic hatred. Niger is one of the world’s poorest countries, and the Tuaregs have suffered greater deprivations than other groups because of the disastrous setbacks they suffered as a result of two major droughts in the 1970s and 1980s. Tuareg have been marginalized politically by dominant Songhay and Hausa groups, living mainly in the west and south of Niger, because they are largely nomadic and live in areas of the country that are remote from the capital at Niamey and from most policy-making centers.

One of the major demands of nearly all Tuareg leaders has been a call for development of the north, to bring it more in line with the rest of the country in terms of sustainable subsistence, education, health care, and participation in governance. Although many donor organizations have come forward with funds to implement new development programs in Niger, the Nigerien government has not yet promoted or approved any that would ameliorate the miserable conditions in the north. Since the famous Niger Range and Livestock Project (USAID) implemented at Tahoua and Abalak in the late 1970s and through the mid-80s, which effectively benefited 18 nomadic families’ pastoral subsistence, no projects have been approved by the Government of Niger to help the thousands of impoverished pastoral nomads in Niger’s northwest regions, and a significant number of these have since been displaced by famine, livestock losses, and political turmoil.

Since the coup d’etat in January 1996, the military leaders have requested international aid, ostensibly to take care of some 700,000 people currently “at risk” of famine in Niger’s northwest, insisting that most of these are farmers. Alternatively, 400,000 people have been reported moving into cities and towns from nomadic northwest regions (which would be mostly Tuaregs), and an American working for the Famine Early Warning System (FEWS) at Niamey admits that “the pastoralists are being squeezed.” The US and France withdrew aid after the coup to protest the overthrow of the democratic government, but France has begun to resume aid to Niger. Many fear that any food aid sent to Niger for famine victims would be illegally offloaded and sold to Nigeria or elsewhere for the profit of government leaders, as allegedly happened during the last two droughts, and that little or none of the food aid would reach the hungry nomads.

The intense violent conflict between Twareg resistance armies and the government of Niger dates back only about four years, but the conditions that provoked it were brewing over a long period of time. One of the most solemn values in Tuareg society is patience; but when Twareg patience wears thin, Tuaregs are forced to seek a solution. Tuaregs have kept their patience now for a hundred years since their people were violently subdued by French colonizers, rising up occasionally to protest their treatment under colonial and independence governments. The present generations have survived only to see their children in tatters, starving, forcibly deprived of equal opportunities with the rest of Niger’s people, violated, and murdered.

Mano’s passing is a signal to Tuareg leaders, scholars, and spokesmen to abandon their anger and frustration over political differences within their ranks and combine their strengths to pursue a real solution for their people, one that will take the national government to task for its lack of action, that will recruit the aid of American, European and other foreign governments to help the Tuareg people out of their misery, and will gain a democratic voice with all the basic rights and privileges that democratic nations enjoy. Mano worked hard for justice, human rights, and to protect Tuareg culture. He was a capable leader, one who could bring people together in agreement, and had he succeeded in making his trip to Niamey to talk with the Prime Minister, he may have brought the Tuareg people one step closer to equal rights and fair treatment. His steadfast vision will serve as a powerful inspiration to others seeking a solution for the Tuaregs.