[dropcap]I[/dropcap]t is important to note that the Amazigh cultural revival refers to the empowerment and greater celebration of Amazigh culture. The Amazigh nation predates all known established civilizations, with rich cultural traditions, languages, and institutions that have survived despite many waves of colonization and attempts at stamping them out. Thus, the answer to the question of the origins of the Amazigh cultural revival is complex and based on reactive stances to Phoenician, Greek, Roman, Arab, and Western European political and cultural invasions that have taken place over the last two millennia.

[ads1]

In this regard Reed Wester-Ebinghaus in Ancient History Encyclopedia argues:

“The Berbers have occupied North Africa, specifically the Maghreb, since the beginning of recorded history and until the Islamic conquests of the 8th century CE constituted the dominant ethnic group in the Saharan region.”

The Amazigh cultural revival was a highly decentralized social movement that evolved into its full force during the 1970s. Its complete roots stretch far back before North African independence from colonialism, all the way back to the invasion of Roman and Arab-speaking warriors in Berber regions, over the span of 2000 years; but for the purposes of the contemporary movement, the past 150 years suffice as its impetus. Spurred by decades, if not centuries, of invasion and oppression, a Pan-Amazigh movement began to form around the desire to revive a largely undocumented yet present culture across North and Saharan Africa.

Amazigh identity

Amazigh identity is formed largely by its language awal, Tamazight. Language is the marker of all cultures, but particularly so with Amazigh civilization. Tamazight Is being recognized by both Morocco and Algeria as an official language in their respective constitutions. This recognition came about after a long period of denial from the governments and society about Tamazight and its connection to Amazigh identity. It ran into several issues. Besides the multiple dialects of Morocco and Algeria, Tamazight was unwritten in the recent past except among the Tuareg in the Sahara.

[ads1]

The first task of the officially recognized Amazigh cultural team in the government was the selection of an official alphabet for Tamazight in Morocco i.e. Tifinagh. Unfortunately, the language has interacted with Arabic for so many years that the two have intermixed. In 2005, a movement was started to teach Tamazight in Amazigh areas. This called for the creation of textbooks and a curriculum to be taught by teachers in Tamazight. Although the governmental ministries dragged their feet in this endeavor, Tamazight TV 8 was created as an Amazigh cultural channel. Clearly, language is a definitive element of Amazigh cultural identity in Morocco and the same applies in Algeria.

The next major defining aspect of Amazigh culture is land akkal. Land has been historically and culturally significant to the Amazigh people. Land conservation is taken very seriously and land ownership balances the fine line of being communal with private property. Additionally, disputes can arise over land ownership. However, a census taken in Morocco in 2014 was controversial to the Amazigh because of the composition of the population as well as Amazigh land location and territory.

The land on which the Amazigh live extends all the way from Egypt to the Canary Islands. This land is called Tamazgha, and the Amazigh believe that it belongs to them. Thus, there are some issues surrounding Amazigh land today since it is such a large component of Amazigh identity and culture.

Another theme central to Amazigh identity is the idea of blood ddam. Family to the Amazigh represents cohesiveness of their culture. Solidarity with other Amazigh people denotes the recognition Amazigh feel in addition to a sense of belonging. Additionally, blood represents sacrifice in Amazigh culture. This sacrifice can represent the earning back of honor, repayment of other sorts, or recognition of significant events. The Amazigh believe that an issue is resolved only once sacrificial blood is spilled. As such, blood is a very important aspect of Amazigh identity and was used in the Amazigh cultural revival movement.

[ads1]

Altogether, the Amazigh cultural revival movement called for a definition and recognition of the Amazigh culture. This movement drew upon the components of language, land, and blood to unite the Amazigh people. In terms of language, Tamazight was decided upon as the official language of the Amazigh people. Another identifying aspect of Amazigh culture is land. The Amazigh see land as central to their society and thus sought governmental protection for their lands. Finally, the cultural concept of blood brought them together for the cultural revival movement. United by blood, the Amazigh people sought governmental recognition of their lands and the official use of Tamazight in the Amazigh cultural revival movement.

On the issue of Amazigh struggle for recognition in Algeria, Amir Akef writes about this country’s recent official change of heart towards Amazigh culture in The Guardian, in a piece entitled: “Algeria proposes constitutional reform.” He first details the official recognition of the culture since 2002:

“Amazigh was granted “national language” status in 2002 and its recognition rewards the efforts of a long campaign hinging on the definition of Algeria’s national identity. In 1949 the issue triggered a serious crisis in the Algerian independence movement. The controversy was papered over when the war of independence started shortly afterwards, but resurfaced when independence was proclaimed in 1962. Hocine Aït Ahmed, one of the original leaders of the independence movement, advocated a democratic state guaranteeing political pluralism. But his ideas were soon thwarted by the authoritarian Pan-Arab credo that prevailed under presidents Ahmed Ben Bella (1963-65) and Houari Boumédiène (1965-1976).

The campaign in favour of the Amazigh language dovetailed naturally with the broader struggle for civil liberties, gaining fresh impetus in the 1980s with the Berber cultural movement. In the early 1990s the authorities grudgingly started to acknowledge its importance. “It took almost half a century, starting from the crisis in 1949, for the Algerian constitution [of 1996] to begin to draw up a more balanced, realistic map of the nation’s identity, though there is still a great deal of ambiguity,” the nationalist militant, then leader of the Algerian Communist party, Sadek Hadjeres, wrote in 1998.”

[ads1]

And later on moves on to discuss the constitutional reform:

“The plans for constitutional reform include setting up an Algerian Academy of Berber Language, tasked with consolidating its new status as an official tongue. Supporters say it would put an end to a pointless source of division, giving rise to various political ills the country could well do without.”

Amazigh struggle for full recognition in Tamazgha

For decades, the Amazigh community has been trying to penetrate into relevant life and culture within North Africa. Their focus on language, land, and blood have had ties to the land and people for thousands of years. The unwritten culture they have built and passed down through generations has shaped every aspect of life. However, since the Arabs have controlled the region, they have historically been ostracized and ignored, being pushed aside while the dominant Arab culture and values have received all the credit and in the process marginalizing Amazigh freedom, standards, and lifestyle. Over the years the Amazigh cultural revolution has been met with obstacles, oppression, and ignorance while trying to gain recognition for their influence on culture and existence as an ethnic group.

In the 1970s more and more Amazigh voices were being projected, arguing for less oppression, more rights, and acknowledgment of the Amazigh culture and ethnicity. These underground activists continued to gain support in the following years, finally breaking through in 1980 with the Amazigh Spring in Algeria: tafsut Imazighen. The Amazigh Spring created widespread awareness within the region. While it may have only been a “Spring” in Algeria, its influence did not go unnoticed in Morocco. The Spring sparked even stronger hope and strength within the Amazigh fight. Supporters of the Amazigh cause were fighting harder than ever for their voices to be heard, their history to be recognized, and their culture to be acknowledged. The flame continued to light the way for more activism in the years to come.

[ads1]

In 1994, the Amazigh movement finally had some acknowledgment by those in power. During a protest on May Day, Amazigh supporters marched with a banner written in the Amazigh language. The activists were arrested and taken in by police. Such an act created outrage within all of Morocco. The media followed the trials and the situation closely, leading the movement to gain national support for Amazigh rights. The nation was finally starting to recognize the Amazigh community’s battle within the country.

The beginning of the revival was in Algeria: tafsut Imazighen

Algeria in response to the aggressive Arabization efforts of the FLN regime which aimed to suppress the Amazigh identity by banning activities by Amazigh militants and the use of Tamazight and its variants, people voiced their discontent publicly.

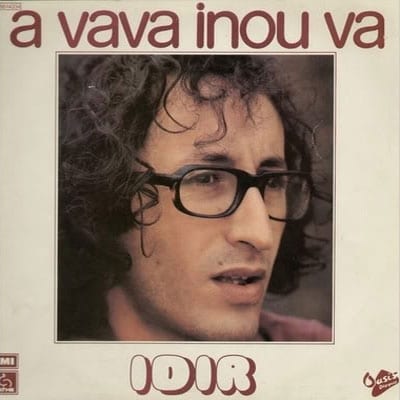

In this context, many Imazighen in Algeria began to push boundaries in their respective fields in the late 1970’s. A primary example of this rests in the album “A Vava Inou Va “ that the late musician Hamid Cheriat, also known by his stage name Idir, produced in 1976, in the period leading up to the Kabylie Tafsut Imazighen. “A Vava Inou Va “ was the first internationally released album by an Amazigh musician in Tamazight, and this artistic creation led to the blossoming of Amazigh music throughout North Africa. The revival of Amazigh literature also coincides with the same period, and the demand that it created for a written medium for Tamazight aided the adoption of the Tuareg’s Tifinagh script and added legitimacy to the movement to recognize Tamazight as a national language in 2001 in Algeria and as an official language in Morocco in 2011.

On March 10, 1980, a conference at Mouloud Mammeri Hasnaoua University in Tizi-Ouzou featuring a Kabyle activist by the name of Mouloud Mammeri was suppressed and the pushback from Amazigh activists led to the mass arrests of its main players on April 20, 1980. Though the Algerian FLN government violently suppressed the strikes following from these events, and the movement did not succeed immediately, it became the critical rallying point for the formation of civil society organizations such as the Rally for Culture and Democracy (RCD) and the Berber Cultural Movement (MCB), which both advocated for greater recognition and acceptance of a distinct Amazigh cultural and linguistic identity and the protection of Amazigh human and legal rights. Later, Tamazight was recognized as one of Algeria’s national languages and these developments also had the collateral effect of adding strength to the general push for the protection of human rights in Algeria. A second political push came during January 2011 as the Arab Spring pushed through the Middle East and North Africa, and this momentum strengthened the social, political and cultural institutions created by the first Tafsut Imazighen.

[ads1]

Tamazight revival in Morocco

In response to the outpour of Amazigh support across the nation and the cries for more Amazigh rights, King Hassan II publicly spoke about the need to teach Tamazight in schools in a speech on August 20, 1994. He stated that the Tamazight language was important to Morocco’s past and culture. Within this speech, King Hassan II was the first Alouite king to finally acknowledge the Imazighen’s importance to Morocco and its development.

In this regard, Karima Ziamari et Jan Jaap De Ruiter write :

« Le discours du Trône du 20 août 1994, à l’occasion de la fête de la Révolution du Roi et du Peuple, est considéré comme un tournant. Dans ce discours, le roi Hassan II annonçait, dans un certain sens, l’ouverture du pays aux trois variétés de berbère. Il se montrait favorable à l’enseignement de ces langues, et, immédiatement après ce discours, les stations TV et radio commençaient des bulletins d’information en tarifit, tamazight et tachelhit. »

However, the battle for rights and recognition still continued into the new century. In 2001 King Mohammed VI declared in his Royal Decree that it was finally time to support the Amazigh cause and therefore created the Institut Royal de la Culture Amazighe -IRCAM-. IRCAM was formed to increase awareness and support for the Amazigh around the country. It standardized the Amazigh language, agreeing to slowly integrate it into schools and the media. Not only did it officially aid the Berber cause, but it also raised even more national support, acknowledgement, and acceptance of the Amazigh identity as being a key player in shaping Moroccan culture. Even with its improvements there was still doubt unto how helpful IRCAM actually was. Some even argued that the organization only limited the Amazigh identity into a small box, not allowing for different forms and less common aspects to flourish. That being said, the main Amazigh movements agreed with the creation of IRCAM and its push for more recognition of Berber identity within Morocco.

[ads1]

While IRCAM agreed to promote the Amazigh culture through schools, the official start of Tamazight being taught in schools did not happen until 2005. The government’s promise was long overdue, being dragged out despite the King’s decree. Even with this, the language was only taught in Berber speaking areas. Nonetheless, the integration of Tamazight into public schools was a huge step for the Amazigh cultural revolution. With Tamazight came textbooks, curriculum, and teachers that all embodied the acceptance and promotion of Amazigh culture.

As Amazigh cultural activism increased, their presence in the political sphere increased as well. Throughout the 2000’s multiple parties have attempted to form on the basis of their common Amazigh identity. Unfortunately, the government has shut those parties down due to illegality of formation of parties based on ethnicity — with Amazigh considered an ethnicity. Even so, there were ways around the ethnic clause. The Movement Populaire (MP) was formed in 1959 to represent the Amazigh, rural and poor Moroccans in parliament and act as a check to the Arabist Istiqlal Party which was hoping to take over power and become a unique party in Morocco, along the communist paradigm. With this in mind, the MP worked closely with Amazigh activists and has mobilized support for the Amazigh movement across the country, advocating for their cultural practices, rights, and recognition. The party have even gained a significant amount of seats in parliament, becoming a strong influence and legitimate party that has direct advocacy for the Amazigh cultural cause.

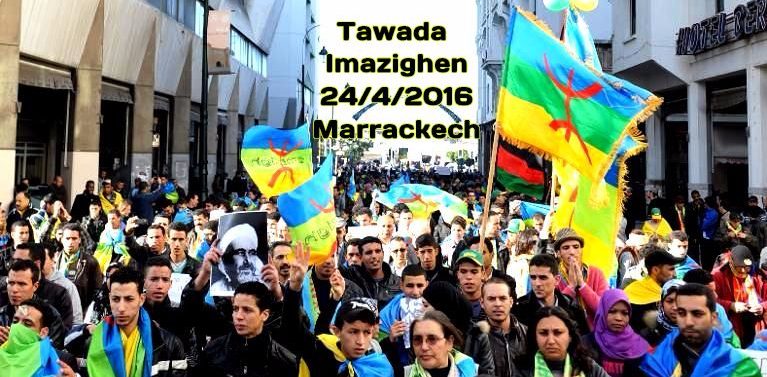

Following the greater influence of the Amazigh in politics, an unlikely coalition formed between them and trade unions and the Islamists, in 2011, calling for greater rights, freedoms, and respect. The support for this coalition came to a peak on February 20, 2011 when the Amazigh were able to mobilize thousands of supporters to protest and rally for their cause. King Mohammed VI quickly responded to these outbreaks —afraid of what was happening across the region with the Arab Spring — and announced that a new constitution would be created. In this the Amazigh gained many rights, with more protections, cultural rights, and more regional governance. One of the biggest feats was that in the new ratified constitution, the Tamazigh language finally became an official language of Morocco. The support from other groups and by thousands of people in 2011 continued to aid the Amazigh in gaining the strength to no longer be pushed aside or ignored. Even to this day they are gaining more influence, credibility, and cultural rights.

From the early 1970s until present day, the Amazigh have vigorously fought for the freedom and recognition of their culture. The cultural revolution has proven that it will not back down until the Amazigh culture is fully recognized and cherished as one of the most important parts of Moroccan history.

Cultural revival is a grassroot movement

In Morocco, one could point to the recurring maltreatment by both the French and the Arab political powers as instigators (the unbalance created by the French Berber Dahir in 1930 and the opposition of the Arab-nationalist Istiqlal party providing merely two examples). Even though they were still legally prevented from identifying as Berber, a magazine defending Amazigh rights began circulating in the 1980s (named Tamazight). By 1991, thirty cultural associations were working in Morocco, each aiming to attain recognition of cultural rights for Amazigh people, their language, and culture.

The cultural revival can be described as a grassroots movement, as it developed on an individual and community level, gradually gaining more political influence and voice. As the cause gained national and international attention, North African governments have found it more difficult to ignore the calls.

But in Morocco, the shift from grassroots activism to government backing may be stalling advancements. Many Amazigh activists feel that the adoption of the Tifinagh script over the Latin script is a subtle way of further separating Berber-ness from Arab-ness in contemporary Moroccan society (many of whom are taught to read and write French before Arabic). Meanwhile, the activists who support government involvement (referred to as makhzenisé by their former colleagues-in-arms), feel these might be small prices to pay for ultimate acceptance.

As far as political implications, the current situation is bittersweet. If states of North Africa want to achieve peace with their Berber populations, they need to not only accept the Berber culture as their own culture, but part of the greater countries’ culture as well. This overlapping identity is still a new idea that is just starting to take seed, and if the gap can be filled between government rhetoric and individual activism, acceptance and fair treatment can be achieved.

What good is it to have

Freemen who sleep in this world of suffering

Wake up, my people

Straighten up, my people

Confront the difficulties of your current situation

A long road awaits you

What good is it to have

Freemen who sleep in this world of suffering…

My friends, my friends

Never forget what

We learned from our parents

My friends, my friends

Let us not forget this heritage

That our parents have left us

Let us keep it fondly

This heritage is our identity. . .

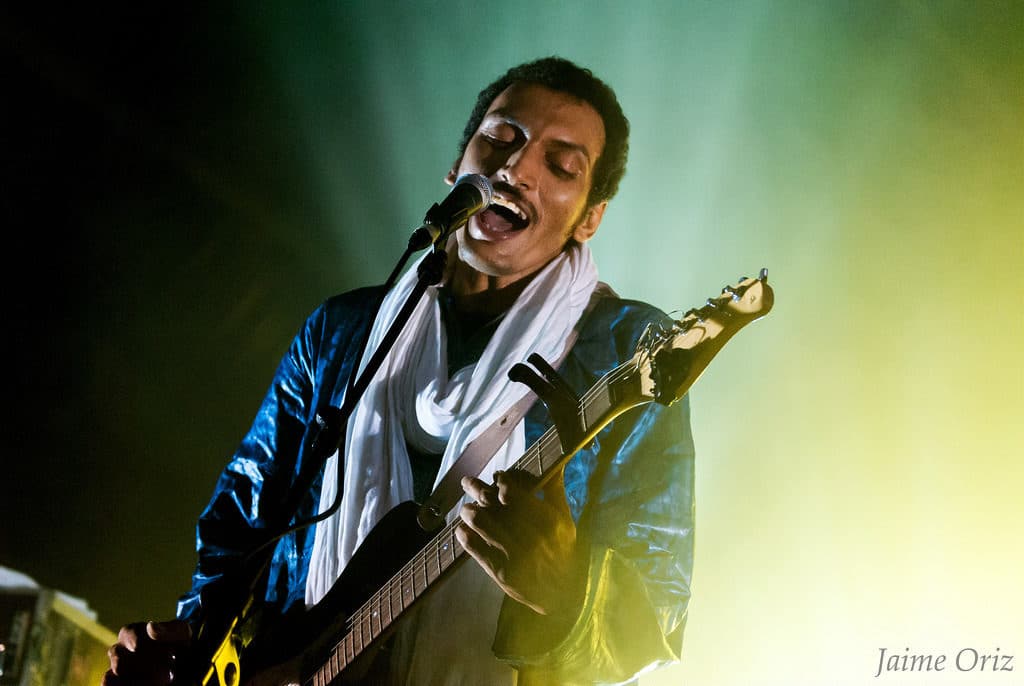

Omara “Bombino” Moctar (Album: Nomad, 2013)

[ads1]

Today, the official IRCAM is in full decline, over the years the Moroccan establishment has used it extensively to subdue the Amazigh and keep at bay the vociferous voices who call for full recognition of Tamazight cultural rights. It is mostly staffed by people from the Association Marocaine de Recherches et d’Echanges Culturels –AMREC-, who have from the very beginning been used as the Amazigh arm of the Moroccan establishment to further its own vision of Amazigh culture: obsequious and subservient.

Since the recognition of the Amazigh language in the constitution of 2011 first in the Preamble:

A sovereign Muslim State, attached to its national unity and to its territorial integrity, the Kingdom of Morocco intends to preserve, in its plentitude and its diversity, its one and indivisible national identity. Its unity, is forged by the convergence of its Arab-Islamist, Berber [amazighe] and Saharan-Hassanic [saharo-hassanie] components, nourished and enriched by its African, Andalusian, Hebraic and Mediterranean influences [affluents]. The preeminence accorded to the Muslim religion in the national reference is consistent with [va de pair] the attachment of the Moroccan people to the values of openness, of moderation, of tolerance and of dialog for mutual understanding between all the cultures and the civilizations of the world.

And also in Article 7:

Arabic is [demeure] the official language of the State. The State works for the protection and for the development of the Arabic language, as well as the promotion of its use. Likewise, Tamazight [Berber/amazighe] constitutes an official language of the State, being common patrimony of all Moroccans without exception.

An organic law defines the process of implementation of the official character of this language, as well as the modalities of its integration into teaching and into the priority domains of public life, so that it may be permitted in time to fulfill its function as an official language.

Ircam was, ultimately, downsized and runs, at the time being, illegally without a governing board (Conseil d’Administration) and it seems that the Makhzen is violating flagrantly its own legislature for such institutions.

In an article entitled: « L’Institut royal de la culture amazighe (IRCAM) va-t-il disparaître? » Reda Zaireg of the Huffpost Maroc Argues :

Dans le projet de loi organique relative à l’amazighe, seules trois institutions sont évoquées dans le projet de loi : le Conseil supérieur de l’éducation, de la formation et de la recherche scientifique, le ministère de l’Education nationale ainsi que le Conseil national des langues et de la culture marocaine.

C’est dans l’escarcelle de ce dernier Conseil que l’IRCAM pourrait tomber. En effet, le projet de loi organique relative au Conseil national des langues et des cultures devrait doter ce dernier d’une super-compétence en la matière, et sera “chargé notamment de la protection et du développement des langues arabe et amazighe et des diverses expressions culturelles marocaines”, selon l’article 5 de la Constitution, qui dispose, aussi, que le Conseil “regroupe l’ensemble des institutions concernées par ces domaines”.

La possibilité que le Conseil national des langues et de la culture regroupe la totalité des institutions concernées par les langues et la culture semble déplaire au directeur de l’IRCAM Ahmed Boukous:

“Nous considérons que le Conseil national des langues et de la culture doit garder l’IRCAM en l’état avec ses missions, son statut, son règlement intérieur, ses moyens financiers, ses ressources humaines, si on veut que cette institution continue de faire le travail qu’elle fait, de manière tout à fait respectable depuis sa création”.

[ads1]

Final word

To conclude, the importance of the recognition of Tamazight as a national language in Maghrebi states previously suppressing it is monumental, given that language is one of the primary tools that the governments and European colonial powers used in Arabization and development to stamp out Amazigh identity. In fact, all political movements to advocate the Amazigh nation can be traced back to language, be it through song, academic discussion, or literature. This ties directly with a primary tenant in the triage of Amazigh identity, language, and also with the importance of all aspects of oral literature in the transmission of Amazigh culture. Thus, the political movement of the Tafsut Imazighen has both propelled forward and gave birth to important cultural vestiges of the assertion of Amazigh identity, leading to the positive developments of the Royal Institute for Amazigh culture (IRCAM) in Morocco, the creation of Amazigh radio, news, and fine arts outlets in theater, literature, and dance and the full recognition of language and civilization in Algeria, as well. Incorporating Tamazight and other aspects of Amazigh identity has occurred since the first recorded colonization attempts by the Phoenicians, and it has survived in this way to the present day, and so it is important to celebrate the appreciation for Amazigh arts in popular culture today in tandem with positive political developments, because their interaction is dynamic.