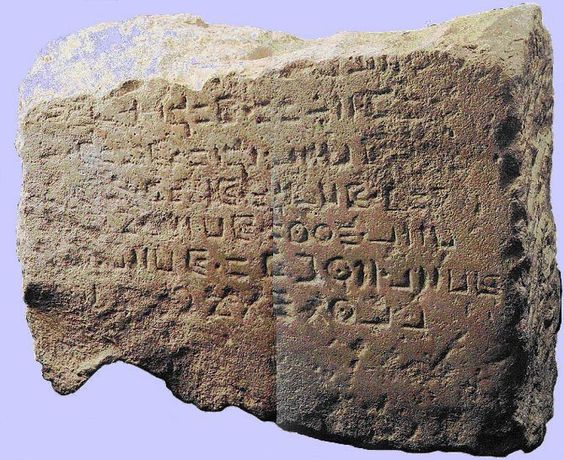

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]ome of the most extraordinary writing in the world can be seen on the wall of a cave deep in the Sahara Desert.

The site is called the Wadi Matkhandouch Prehistoric Art Gallery, near Germa in Libya. It’s startling to find any evidence of human presence in such an inhospitable place, so far from what we think of as civilization.

And, frankly, this writing, in a script called Tifinagh, doesn’t look much like what we think of as writing. It’s a meandering string of simple, bold symbols, some of which look more like mathematics than writing: Is that a plus sign? A zero? A percentage, sign, for heaven’s sake? Is this writing from the past, or the future?

This twisting strand of language looks so old and so deep it might just be the DNA of writing. Oh, and did I mention that the symbols or letters are in such a strange and vivid red pigment that they look as if they’ve been written in blood?

Tifinagh, the script used to write the Amazigh (or Berber) languages of North Africa, is a reminder, like many endangered alphabets, of a lost kingdom. But it’s also the visual symbol of a dream. Some 2,000 years after that writing was daubed on the wall at Wadi Matkhandouch, after centuries of being invisible, suppressed, and even banned, it has finally begun to reappear. One of its letters, yaz, which hauntingly resembles Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, is a central symbol in the design of the current Amazigh flag.

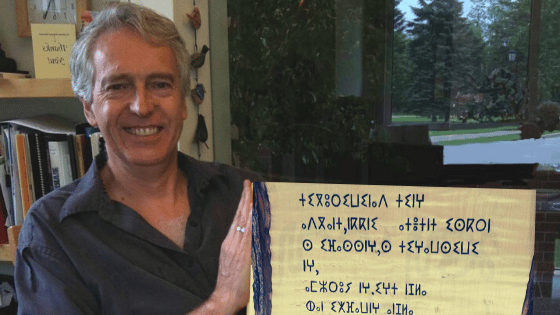

And as such, Tifinagh is part of a global movement. All over the world, a remarkable phenomenon is taking place: people are starting to use writing systems that have not been in general use for decades, even centuries. Why? What is it about a way of forming letters that can inspire such a sense of connection, warmth, even passion?

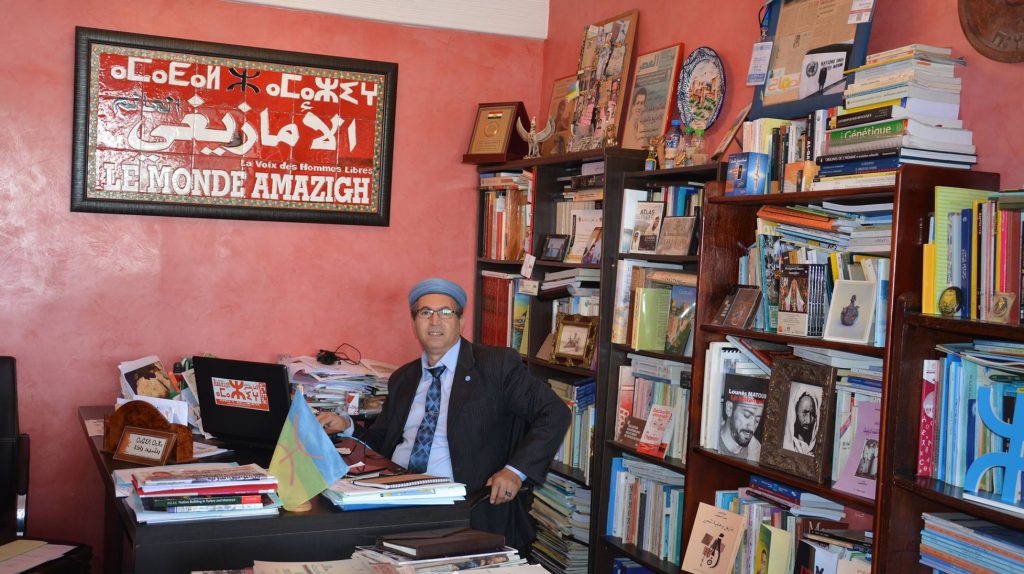

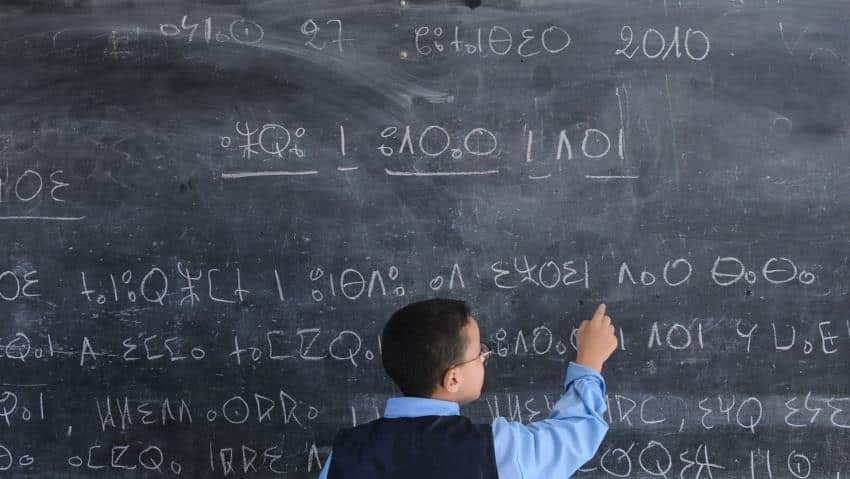

The answers vary from place to place, but the Tifinagh script, specifically in Morocco where I’ve had the chance to observe its resurgence at first hand, presents a fascinating case study in script revival.

Script revival is, by and large, the effort of small, passionate groups or even of individuals, who are largely ignored, obstructed or even opposed by their national or regional governments. As these revivalists are almost by definition in a cultural/economic minority, they also tend to lack the funding to support extensive efforts.

The Moroccan government has officially accepted the Amazigh language and the Tifinagh script, and though some Amazigh protest that more could be done, and should have been done much sooner, the fact remains that we have the chance to see what initiatives are under way in Morocco, how well they are working, what difficulties they face, and thus whether they might work elsewhere.

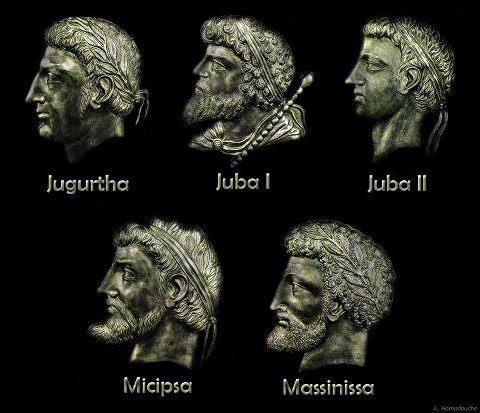

Two thousand years ago, much of North Africa belonged to the Amazigh. Amazigh, in the Amazigh family of languages, means “noble men,” but the Romans gave them the condescending name barbari, meaning “barbarians,” from which emerged the name Berbers. The Amazigh call the region Tamazgha, a broad area, not defined by national borders, where the Amazigh language was or is spoken—from Egypt in the East to the Canary Islands in the West, to Niger in the South. Sometimes southern Spain is also included.

The Amazigh coexisted with the Phoenicians and the Carthaginians to such an extent that the early Amazigh script, called Tifinagh, may have influenced the development of Phoenician—and as Phoenician strongly influenced the birth of Ancient Greek, some Amazigh researchers think of their script as the fountainhead of European writing.

By 200 BC, Rome had defeated its rival Carthage and occupied all the Mediterranean coast north of the Atlas Mountains, to this day an Amazigh stronghold.

Eight hundred years later the Arabs swept west, unifying North Africa with southern Spain in what became known as the Grand Maghreb, the Land in the West or the Land of the Sunset.

The Maghreb, even if it was an Arab creation and administration, unified Amazigh territory, giving it strength and significance. On the other hand, the co-opting of intellectual, artistic and religious leadership by the Arabs, especially in the cities, meant the subordination of the Amazigh, especially in terms of language. To the Arabic ear, the spoken Amazigh languages sounded, well, barbarous, and were heard mainly among the nomadic families and in the mountain villages. And as the beautiful script of Islam scrolled across the region, Tifinagh fell almost entirely out of daily use.

In the nineteenth century, new colonial regimes emerged in the region. The official administrative language of Morocco and Algeria became French, with Arabic second and Amazigh actively, sometimes brutally suppressed—a situation that lasted well over a century.

Tifinagh was saved by the mountains and the desert. The Arabic influence, and later the French, primarily affected the cities and larger towns. Farther inland, the Touareg in particular never stopped using Tifinagh. The women, who were responsible for their children’s education, not only taught the letters but incorporated them into the distinctive and complex Amazigh tattoo symbols, and into the equally distinctive jewelry, fabric and carpet designs.

This complex, deep relationship between a people and their writing symbols shows what a mistake it is to think of writing as merely a means of recording the sounds of speech. Among the Amazigh, as among dozens of other cultures, writing has an extraordinary depth of appeal and identification, like the head on coinage or on postage stamps, or the colors and design of a flag.

So it was in the mid-1960s that when a group of Kabyle (that is, Algerian Amazigh) writers, journalists and activists living in Paris formed the Amazigh Academy to re-establish the Amazigh identity and Amazigh rights in the face of centuries of suppression, they decided to revive the Tifinagh script as a specifically Amazigh form of writing—and placed one of its characters, the yaz, at the heart of the Amazigh flag they designed.

Next time I’ll discuss what I found in Morocco, and what I learned by interviewing a wide range of Amazigh from Fez to Marrakesh. Is the Moroccan initiative in language revival, both spoken and written, working? And if so, what can other minority and indigenous cultures learn from it?

[ads2]