By Nuunja Kahina on June 26, 2015 — You will, by now, have read one article or another about the French intervention in northern Mali, the general gist of which is that Islamic extremists trying to take over the country and destroy Mali.

You will have read about music being banned and a strict interpretation of shari’a law being implemented in the northern region, with numerous Islamist factions taking control. All true, and the fears of secular Malians who oppose these actions and terrorist activities are legitimate, but there is another story from the region that began much earlier and has been scarcely covered by mainstream media.

Other story

Besides shedding light on this story, I hope to remind people that it is entirely possible to be a victim while carrying out atrocities of your own. We tend to prefer the simpler narrative of 100% good guys vs. 100% bad guys, but the reality of most conflicts is messy and rarely black and white.The reality of most conflicts is messy and rarely black and white

There are multiple movements currently vying for power in Azawad (a territory in northern Mali), and the conflation of indigenous, secular, nationalists with the various Islamist groups – which are mainly funded by and made up of outsiders to the region – only serves to misinform the current situation and leads to misunderstanding.The only things these groups have in common is an opposition to the Malian government, but that does not mean they support or agree with one another, and understanding the distinctions between them is crucial for a clearer picture of what’s happening in Mali.

Independence

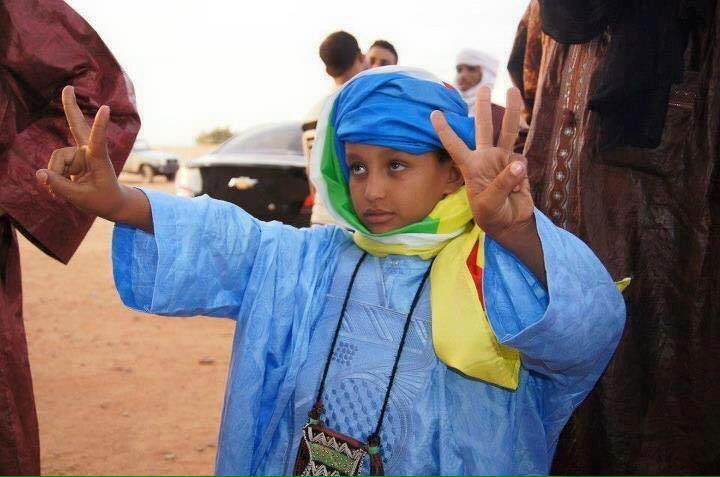

While the goal of most Islamist groups is to establish an Islamic state, Tamasheq civilians (a subgroup of the Tuareg peoples, who live in an area that stretches from the Sahara to Sudan) and most of the population of Azawad simply want to live in peace: “Azawad independence means ‘no more state interference in our lives.” This sentiment is echoed by some of our most well-known Malian musicians and bands, such as Khaira Arby and Tinariwen. To promote these incredible musical traditions and secularism in Azawad, we must understand the context and origins of the conflict.In January 2012, a civil war began in Mali between Bamako and the people of its northern region Azawad, represented by National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (known by its French acronym MNLA). By April, Azawad was declared an independent state by the MNLA, which sought to establish an independent Saharan state with a secular and democratic government. These developments went underreported by the mainstream media until the recent French intervention in Azawad, in which over one hundred people were killed on its first day.

Colonialism

The most populous indigenous ethnic group of the Azawad region are the Kel Tamasheq, who are part of the larger Amazigh people living in North Africa. The Kel Tamasheq, also called “Tuareg,” are nomadic, and live in the Sahara, divided by the colonial borders of Mali, Niger, Algeria, and other states. Before French colonialism of the Sahara ended, a group of Tamasheq and other Saharan leaders wrote a letter to French General De Gaulle asking for a Saharan state of their own.When they found that they were to be split up between several countries and that French colonialism would simply be replaced by another form of foreign occupation, they could accept their exploitation no longer. In Mali alone there have been four major uprisings of the Kel Tamasheq since formal French colonialism ended: in 1963, 1990, 2006, and finally in 2012.Tinariwen’s Soixante Trois refers to the first uprising of Azawad, and talks about how they will continue to rebel against Malian rule. A sample of the lyrics:

’63 has gone, but will return

Those days have left their traces

They murdered the old folk and a child just born

They swooped down to the pastures and wiped out the cattle…

’63 has gone, but will return

Exploitation

Mali and Niger, who have weathered the strongest resistance from the Kel Tamasheq, have continually exploited Tamasheq lands – mostly for gold, oil and uranium, which are usually sold to France – and underdeveloped their northern regions. Documentary filmmaker Akli Sh’kka has recorded the experiences of some of the Tamasheq people in his short film Imshuradj, a Tamasheq word meaning “people without a country.”

In his admittedly leading questions, he refers to the massacres which killed hundreds of people in Azawad, the poisoning of wells and the killing of animals, the last two of which are lethal in the desert. Confirmation that the Malian government is capable of committing the atrocities reported by these Tamasheq civilians can be found in its willingness to bomb civilian populations, even refugee camps, as they did during the MNLA’s fight for Azawadien independence. Actions like these reveal a wanton disregard for human life – Azawadien life – on the part of the Malian state. In addition, discriminatory killings targeting Tamasheq civilians on the basis of their ethnicity have been reported.

White versus black?

One of the misconceptions of the Azawadien conflict is the idea that it is rooted in the racism of‘white Tuaregs’ vs. ‘black Africans’: that the Kel Tamasheq simply cannot bear to be ruled by Black, southern Malians. However, a significant number of Kel Tamasheq are dark-skinned people who would nearly universally be considered Black (to my knowledge, most Kel Tamasheqs are dark-skinned), and as far as I’m aware the lighter-skinned ones do not see themselves as white, so this racial analysis sounds uncomfortable like the common tendency to interpret any friction between people as “tribal” conflicts.

The conflict between Bamako and Azawad is rooted in economic exploitation, a history of violent oppression, and Indigenous Saharan claims to the land, rather than in the purported white supremacy of an indigenous African people. The Tamasheq, like other Imazighen, are neither Arab nor European. Furthermore, Azawad was never intended to be an ethnic state only for the Kel Tamasheq, but inclusive of all other ethnic and linguistic groups residing in the region.

Soldier-musicians

The decades-long struggle of the Kel Tamasheq in Azawad has been most popularly represented by the ‘desert-blues’ band Tinariwen, winner of the 2012 World Music Grammy for their albumTassili. The band was formed in the 1980s with a group of five young Tamasheq living in exile in southern Algeria, soldier-musicians who were involved in the 1990-94 Tamasheq uprising against both Mali and Niger.

They were trained in military camps in Libya with the promise from Gaddafi that he would help them create an autonomous Saharan state of their own, though in actuality Gaddafi only sought to exploit the dispossessed Kel Tamasheq to further his own imperialistic ambitions. Tinariwen, which has always supported Saharan self-determination and independence, rose to global prominence after meeting the French band Lo’Jo in 1998 and began touring Europe soon after.

Yet this international fame has not separated the members of Tinariwen from the struggle for freedom in their homeland of Azawad. Their Amazigh nationalism and desire for independence was as strong as ever when I got the chance to have a chat with the band members – between their cigarettes and atay – during a recent tour.

The song Tenere Taqqim Tossam is about the love of the desert. Here are some lyrics which come from Tinariwen’s site in official English translation:

The desert is mine

Tenere, my homeland,

We come to you when the sun goes down

Leaving a trail of blood across the sky

Which the black night wipes out

One of the members of Tinariwen was even kidnapped by one of the Islamist groups rising to power in Azawad, one of the groups some of those unfamiliar with Mali mistakenly equate with the Kel Tamasheq and MNLA.

Western foreign policy

The takeover of the new state of Azawad by Islamist factions such as Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) was not without external involvement with an interest in fostering terrorism, corruption, and drug trafficking in the region (see “How Washington helped forter the Islamist uprising in Mali”). In particular, The role of Algeria and Western foreign policy in particular have proven key to the Islamist takeover, as has the Qatarian backing of Islamist groups.

All of these external interventions are underpinned by specific economic or political motives. France, the former colonizer, is defending one of its sources of phosphate, oil, and uranium, of which neighbouring Niger is one of the greatest suppliers, and the success of an Azawadien state is feared because it is believed it would incite the Kel Tamasheq in Niger to rise up, too, as they have in the past.

Meanwhile, Algeria and the surrounding countries with Tamasheq populations seek to quell the rise of Amazigh power and prevent separatist revolutions within their own borders.

Outsiders

With the justification of preventing terrorism and Islamism radicalism in the Sahara, and with the added motivation of the Algerian hostage crisis, France has deployed nearly 2,500 troops in the region with hundreds more arriving from ECOWAS. Is the goal to stem the spread of shari’a law and Islamic theocracy or crush the dreams of a secular, democratic state of Azawad, and kill thousands in the process? Perhaps both.

The MNLA and Azawadien civilians do not want to live under AQIM or under an Islamic law enforced by brutality, but what this intervention really means for the Kel Tamasheq is that – once again – they will be killed en masse for the economic and political goals of outsiders. Their desire for self-determination, linguistic rights, and the freedom to practice their culture will not come to fruition, not now. The French invasion, fully supported by neighboring West African states, serves to strengthen the ties between the colonizer and the colonized.

European map

An independent Azawad has dangerous implications. Azawad challenges the colonial borders drawn by Europeans at the Conference of Berlin during the Scramble for Africa and provides the first such significant challenge since the independence of South Sudan. Recognizing Azawad would have dire implications for the discriminatory Arab nationalist regimes of North Africa, whose Indigenous Amazigh populations have a close connection with their Kel Tamasheq sisters and brothers.

The AU and ECOWAS have backed Mali in the conflict — the AU formally refused to recognize Azawad after their declaration of independence — and fully cooperated with the French invasion. Thus Mali and other African states are not yet ready to break ties with their “former” colonial powers, nor to defy the European map of the continent.

Resources

For the Malian state as well as France, economic exploitation has continually been shown to take precedence over the value of human life with respect to the residents of Azawad. The adoption of European capitalist structures in “post-colonial” Mali allowed a particular elite of those in power to conceptualize the Azawad region as a resource, allowing the state to distance itself from the very humanity of Azawadiens.

Livelihoods and ecological integrity in Azawad thus become secondary to the capital accumulation resulting from resource extraction and sale. The human cost of the current attacks on Azawad from France, Mali, and ECOWAS are, in comparison, considered unimportant.

Not simple

There is a positive role that the Malian state and citizens can play for Azawad, by advocating for regional autonomy or even independence and speaking out against the war crimes and human rights abuses perpetrated by the Malian state against Azawadiens. Regardless of the territorial status of Azawad, for any reconciliation to occur the legitimate grievances of the Kel Tamasheq need to be recognized and addressed by Mali. Secularism, peace, and stability will only come to the region by addressing the very real exploitation and discrimination experienced by the Tamasheq and other Azawadien citizens.

As I wrote at the start of this article, we prefer the simpler narratives, but reality is rarely black and white.

Source: thisisafrica