“[dropcap]T[/dropcap]oumast.”

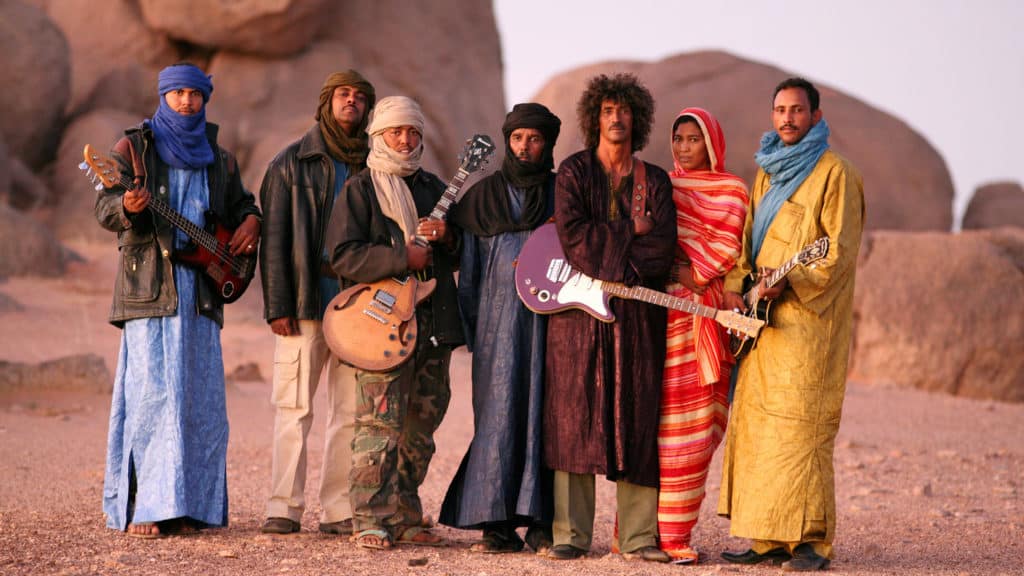

A word from the Tuareg language, Tamasheq, meaning “identity.” A word that Moussa Ag Keyna, a Tuareg guitarist, chose as the name of the band he founded because he “was part of the Touareg rebellion, where everything… (they) did was for the Touareg identity.” Keyna claims that during the rebellions, “even music was created in order to give existence to our identity.”

Keyna is one of the many Tuareg guitarists during the rebellions that contributed to the creation of a new genre of music called Tichumaren. The name of this new desert blues genre was “derived from the French word chômeur, meaning the jobless or unemployed,” a word that reflects the adverse condition of the Tuareg people in modern times. Tichumaren emerged as a tool to reconnect the Tuareg people and redefine the

Tuareg contemporary cultural identity.

Tuareg guitarists use Tichumaren in order to compile their emotions and produce compositions that amplify the Tuareg people’s daily lifestyle and struggles. With the exceptional ability to adapt centuries-old techniques developed on traditional instruments, and use them on the modern amplified electric guitar, Tichumaren molds tradition to fit perfectly into the cavity of modern times. As a result, the art of Tichumaren is able to keep Tuareg tradition alive through the obstacles in place by post-colonial modernization and globalization.

However, many questions arise as to why there was a need for this source of revival and preservation to begin with. How did the Tuaregs preserve their culture prior to Tichumaren? What brought about the need for a Tuareg existential revival? Where did this contemporary void that Tichumaren works to fill stem from? In an attempt to make sense of the circumstances that lead to the emergence of Tichumaren, as well as the role

this new genre plays in the Tuareg tribe, it is imperative to consider the previous means of cultural preservation, the historical context in which the genre was created, and the various obstacles and intricacies that the Tuaregs were faced with during this period.

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]ating as far back as the first millennium BCE, the Tuareg—an indigenous nomadic Amazigh (berber ethnic group) tribe—are known to other tribes and scholars as the masters, warriors, and enduring inhabitants of the Saharan desert. From the paintings depicting their daily lifestyle and their writing system—Tifinar—found on cave walls to the genetic evidence pointing to Ice Aged origins and reaffirming their millennia old traditions of nomadism, the vast and complex history of the Tuaregs is constantly being uncovered by historians through various explicit primary mediums. For the Tuaregs though, in the centuries before the emergence of Tichumaren, poetry by oral tradition was the most esteemed form of cultural preservation and of passing down their history through generations. My father, a Tuareg man who grew up spending his summers in the Saharan region of Northern Niger, always reminisces his time through the poetry he was taught in those days and attests that in the harsh lifestyle of the desert, the poetry was always a means to “soften the heart.” He elaborates by explaining that poetry worked to remind them of their humanity and revive their emotions in times of suffering.

[ads1]

In addition to naturally being used amidst the daily lives of the Tuareg, poetry was also used by the people to capture these quintessential moments and the shared values, which defined their lifestyle. As Seligman writes about in his book, Art of Being Tuareg, Tuareg poetry “explains values and customs, ideals and sentiments, religious and moral sense, relationships between the sexes, and the awareness of social and environmental realities.” He, additionally, makes note of an interesting aspect of poetry in Tuareg society in which the Tuaregs resist writing their poetry (even though they have a script—Tifinar), as they perceive paper as too “transitory” and “perishable,” in comparison to “the noblest attributes of mankind—the mind and memory.” Hence, even when Tuaregs used poetry to pass down their culture from generation to generation, they did so “from one singer to another over the centuries.”

Singing poetry is a crucial factor in cultural preservation for the Tuaregs. From childhood, Tuaregs attended communal poetry readings, where elders and children alike would come together and recite poetry to each other. Known as “Tishiway,” poetry was thoroughly embodied and reflected into actions by the Tuareg. Tishiway itself comes from the word “awey,” which translates to “to carry… to go for a period of time … (and) to recite or compose a piece of verse.” In his book, Poésie, Langage, Écriture de L’Ethnographie des Touaregs à une Anthropologie de la Poésie Orale (Poetry, Language, Writings of Ethnography of the Tuaregs in an Anthropology of Oral Poetry), Dominique Casajus theorizes that “the third meaning seems linked to the first two by the idea that to recite a poem (to recite it internally if one composes it) is to wear it, to take responsibility for it during the time of its recitation… a poem appears… as a verbal object whose proferation is inscribed in time.” However, confining the manifestation of Tuareg poetry to a constrained time period does the practice injustice.

Tuareg poetry escapes the limitations of time and is constantly being actualized through the daily practices of the Tuareg people. Serving to educate the youth of their ancestry and heritage, whilst constantly reminding the elders of the reasons behind their values and customs, poetry empowered all generations, simultaneously, with a powerful sense of pride and unity. Additionally, poetry worked to connect the generations not only through the impactful meaning it held, but through creating the bonds between the elders and youth in real time interactions and group recitations. At its core, poetry interconnected generations as well as served as an innate form of cultural transmission and preservation for the Tuareg people. Unfortunately, with the rise of French imperialism and the aftermath of colonization, poetry began to gradually lose its ability to connect the generations and the Tuareg tribe as a whole.

[ads1]

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]uring pre-colonial times, the French imperialist invasions challenged the preservation of the Tuareg culture more than ever. From 1890 to 1894, one of the greatest foreign travellers of the Sahara, Fernand Fourneau, explored the Tuareg inhabited regions of In-Salah and Tidikelt in present day Algeria, and the Air region in present day Niger. Fourneau recognized the importance of these regions “as a key to the control of the Sahara” for the French. With a yearning for power, the French attributed a great weight to Fourneau words and “decided to use force against the Touaregs, as the only method likely to give them control of the desert.” With a history of perseverance and resistance, the Tuaregs progressively transformed into “the most fervent colonial enemies of France.”

Withstanding fights against the French for decades, with the collapse of the Ottoman empire came the eventual failure of the Tuareg revolts and the French were able to implant their forces and instill their governments in the Tuareg inhibited regions of West and North Africa. Under colonization, not only did the Tuareg lose their indigenous territories, but their confederations weakened as well. The French epidemically exploit various valuable resources found under Tuareg ancestral lands. Moreover, seemingly as revenge for their persistence to resist pre-colonization, when African countries began to gain independence in the 1960s, the state of the Tuareg people worsened. With the creation of the states of Niger, Mali, Algeria, Libya, and Burkina Faso, the Tuareg tribe was split amongst five newly formed nations and turned into a powerless minority across the board. Beyond the severe droughts and drastic economic hardships facing the Tuareg due to the novel deprivation of work as a result of a new post-colonial economic system, the Tuaregs now encounter political marginalization in the nation-states as well, all of which exacerbates the desperate state of the Tuareg people. Thus, the aftermath of colonialism would haunt the Tuareg people for decades to come.

Beyond the tangible struggles and shift in daily life of the Tuareg people there lies an imperceptible shift in culture and its consequences. By creating divisional, strategic borders, the Europeans worked to not only segregate the confederations of the Tuareg tribe, leaving them weaker, but it ultimately stripped the Tuareg of their nomadic lifestyle. This, furthermore, restricted their economic system, which depended on open-end travel through the Sahara. As a result, according to the Historical Dictionary of Niger, “colonization unsettled Tuareg Society in more serious ways than it did sedentary societies.” Not only were the Tuareg becoming increasingly and disproportionately unemployed, but they were

intentionally targeted and suppressed culturally as well. Moreover, Tuareg regions are left lacking infrastructure, schools, electricity, clean water, and many more necessities that other parts of the countries benefit from. As a result, there was a growing and justified conviction “among the Tuareg that they were singled out for persecution and discrimination and were more marginalized than other ethnic groups in the distribution of state benefits.” With this sentiment amongst the Tuareg in all five of the countries now left with a minority population, fighting for their human rights became nothing less than compulsory for the Tuaregs.

For these reasons, and many others, there have been a series of Tuareg rebellions (1962–1964; 1990–1995; 2007–2009; 2012) in both Mali and Niger. Along with the rebellions, the gradual annihilation of the Tuareg culture operated to create a new disconnect between the elder generations, the new generations, and the diaspora; a disconnect further caused by the different stages of interaction with the culture, of feeling dissent, and of understanding the modern state of the Tuareg people. From their hardships to the new disconnect amongst the tribe’s generations, the Tuareg were in dire need for a revival of their identity. With an increasing unemployment rate and decreasing population growth, the Tuareg existence was suddenly dissipating. Borders created overnight, the Tuareg culture and unified state

was abruptly transformed. The Tuareg needed a new tool to connect the generations, as poetry once did, while simultaneously build bridges across the divides within the tribe and reestablish their cultural identity in a time of marginalization. Hence, the rebellions led to the emergence of the desert blues genre named after “unemployment,” Tichumaren, a tool that connects the people and redefines the Tuareg contemporary cultural identity.

[dropcap]U[/dropcap]nveiling a new realm of emotions and power, Tuareg musicians transformed their cherished poetry practices into a novel emblematic and revolutionary form of art that we now know as Tichumaren.

Tichumaren’s modernity and global reach make it more resonant and effective than poetry, as it is able to transcend the obstacles of physical disconnect in place due to the displacement and the diaspora of Tuaregs.

Additionally, with the exceptional ability to adapt centuries-old techniques developed on traditional instruments, and use them on the modern amplified electric guitar, Tichumaren molds tradition to fit perfectly into the gap created by modern times.

[ads1]

Surpassing the physical disconnect among the Tuaregs, however, is the emotional detachment of the younger generations from the elders. Bombino—an internationally renowned Tuareg guitarist—captured the

disconnect between the generations explicitly through Tichumaren. In his song, “Akhar Zaman” (“This Moment”), Bombino sings about the pain he feels due to the youth’s disconnection from their culture; “far from your ancestral culture, your personality disappears, along with your spirit.” Tuareg guitarists are conscious of this disconnect and actively use Tichumaren to bring it to light and mend the divide. Singing about the state of the Tuareg people, Tuareg guitarists are able to convey the distress and desperation of the tribe as a result of persecution and neglectance by their post colonial governments.

Thus, Tuareg guitarists use their instrument as a symbol of hope for their people. When asked about the role of his music in the rebellions, Bombino stated, “I do not see my guitar as a gun but rather as a hammer with which to help build the house of the Tuareg people.” On that account, one can acknowledge that Tuareg music functions in a similar manner as poetry in that the people use it as a means to find peace and tranquility in the chaos of the world. However, Tichumaren’s modernity and global reach make it more resonant and effective than poetry in today’s era

What validates Tichumaren as a tool to reconnect the Tuareg people is encapsulated in the various functions it serves. Tichumaren often works to amplify the poetry once spread through oral tradition and group recitation. Many guitarists use their lyrics to serve as memoirs for martyrs of the rebellions and leaders of the resistance to French imperialism. Furthermore, Tichumaren is a form of storytelling that has the ability

to detail events while evoking emotions in its listeners. From stories of the massacres and lynchings during the rebellions to those exhibiting the simple and happy lifestyle of the Tuareg pre-colonialism, Tichumaren

allows for listeners to internalize the Tuareg existence and relive their rich history. The first Tuareg guitarists, such as Ibrahim Ag Alhabib, the founder of Tinariwen, a Grammy Award-winning Malian Tuareg band, started off with handmade guitars from cans and threads that they would use to reproduce traditional Tuareg music. Ag Alhabib mentions that the guitarists never lost hope. Learning from each other in refugee camps, the guitarists always used their music to spread hope of a day when the Tuareg would return home and rebuild their society. However, along with hope, guitarists used their music to awaken the Tuareg people of the situation they are all in and their responsibility to fight for their freedom through unity. Tinariwen sings in one of their songs directly to the Tuareg people, “you are all tied to the same pillar.. you know the suffering, your brothers and sisters are also tied to it and only the union can free you.” A member of Tinariwen explains

that “this song reminds us of all of the hardships we have endured… our tents that were lit on fire, our relatives that were burned, that was the role of this first song.” In their own words, Tinariwen transmitted a message to the people “to make them aware of what they were enduring and to inspire them to react. This was true to many Tuareg groups across the Tuareg ancestral lands. In fact, according to Bombino’s bandmate and

friend Koutana,

“The sound of the guitar arrived in Tuareg lands in Niger and Mali from an Algerian refugee camp, via a revolutionary cassette in 1982. Koutana, who was there, says that that cassette sent shock waves through the Tuareg communities, that both the raw sound of the guitar, and its status as a political change agent — allied with messages of revolution and self-determination — made a strong impact on the nomadic Tuareg.”

From the start, the role of Tichumaren was to invigorate the Tuareg identity, revive their hope, instigate political change, and rekindle a revolutionary reconnection between the generations and with the diaspora that they lost due to imperialism. The violent response of the governments in the countries where Tichumaren mobilized the civilians to stand up for their human rights attests to the influence and potency of Tichumaren as the tool, which resurrected the Tuareg people and culture. In Niger, during the second Tuareg rebellion, “government forces killed two of Bombino’s musicians,” forcing him and many other Tuaregs into exile. Musicians are one of the most targeted Tuaregs by governments in both Niger and Mali, speaking volumes to the power Tichumaren holds. When trying to go home from exile, members of Tinariwen “didn’t have weapons… didn’t have anything,” yet their “intentions (to return) were discovered” before they even left Algeria and many of them were arrested. Tinariwen’s music returned home before Tinariwen could. The music impacted the people in Mali in such a way that they “became a threat to the Malian authorities, to the point that it was even forbidden to listen” to their songs. Hence, Tichumaren’s power to effectively reunite the tribe across borders and foster a substantial emotional interconnectedness amongst all Tuaregs regardless of generation, location, or experiences—lies in its ability to rapidly reach a global audience.

[ads1]

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hen asked how she first heard Tinariwen, a woman from a small village in the desert said she heard “a man playing them on his radio.” Silvia Balit studied modes of communication in the Sahel region, where many Tuaregs reside. She proposed that “communication is a product of culture and culture determines the code, structure, meaning and context of the communication that takes place.” With regards to Tichumaren, however, it is evident that communication was not a product of culture after all, as it was the dwindling of culture that created Tichumaren. Tichumaren is a form of communication that Tuaregs used to reestablish their culture. Coincidingly, ethnomusicologists understand that “analysis of the music being produced by a society reflects the current and historical psychological landscape or cultural identity of that society and its members.” Yet, Balit is valid in that the existent Tuareg culture before Tichumaren, such as the

poetry and the traditional instrument sounds, did influence the “code, structure, meaning and context of the communication” that takes place through the new music.

In “Communications Channels in the Sahel Using Mauritania, Mali, Niger, and Chad as a Case Study,” the authors argue that due to the ancient cultural histories of the Sahel, “successful communication within

Africa depends largely upon consideration for the cultures present within its communities.” Though this is true, their reasoning is problematic as they propagate that “whereas a Western communicator is most familiar with modern forms of communication… many of the impoverished nations of Africa cannot rely on technology for a constant source of information.” To begin, these researchers choose to generalize the entire African continent when speaking of technological advancements, an aspect of society that is at extremely varying levels of development in the different African nations. Most important to notice, however, is that they completely overlook the reasons behind the forms of communication prevalent in these nations and that the people choose to use. In the case of the Tuareg, it is not a lack of technology—as technology is used to mass produce and spread the music—that makes them use music as their form of communication, but rather it is

the intentions behind their message.

According to psychologist, music has the unique ability to “transmit social information across distance to a number of people at once.” Additionally, “it allows a group to communicate without speech or direct interaction and, with the proper tools, enables this to happen across a much greater space than these other routes would allow”. Moreover, psychologists conclude from their studies that people respond emotionally to music as a social phenomena that bind us together into groups. Thus, the innate characteristics of music, which poetry did not possess on its own, serve to solve the dilemma that striked the Tuareg people. Accompanied by the strong interlacing of tradition with modernity as well as the use of emotional and resonating lyrics, Tichumaren reaches a multidimensional, higher strata means of connecting a group of people who were growing detached and despondent.

[dropcap]E[/dropcap]ssentially, with the innate musical ability to convey and widely distribute messages as well as its intricate embodiment of the Tuareg heritage and resilience, Tichumaren resolves the obstacles facing the Tuareg by transcending the barriers among generations, the borders created by imperialists, and the unforeseen transformation of Tuareg culture. Precisely, when faced with a time of hardship wherein the traditional methods were ineffective, the Tuareg people discovered a new avenue by which they liberated themselves and overcame their existential crises. Tichumaren, the driver of the Tuareg people’s renaissance.