One of the most unique countries in Northern Africa and the Middle East is, undoubtedly, Morocco, not simply because of its many different coexisting identities and cultural roots, but for what these influences have blessed this country with, in the long run. There is a persistent question as from where this unique status stems from? These influencing peoples and cultures came from many different origins to Morocco, yet left different legacies throughout its history which brings about the question of how a legacy of an invading or visiting country or religion can result in influencing culture, traditions, and even religion in such a profound way?

Strong common denominators

At the root of it all of these different influences that come from colonialism, migration, trade or invasion, there are some very strong common denominators that enabled the two oldest foundations and influences of Moroccan culture i.e. Amazigh and Jewish to persevere with their influences on culture and values until today. Morocco is widely known as an Islamic nation, but even before the arrival of Islam to Morocco in 694, the Amazigh tribal people were the main inhabitants of Northern Africa, in general.

[ads1]

After the destruction of the second Jewish temple in 70 AD, the population of the area of Palestine, at the time, fled mostly to Northern Africa, besides other places such as Asia, Spain, and the Middle East, where they found a very friendly reception for their way of life and religion. They came to a Roman Occupied Northern Africa yet found mutual respect and understanding that resulted from the meeting of Jewish and Amazigh tribes and their related civilizations and were able to create a very strong and influential base to not only the Moroccan history, and way of life but, also and most importantly, to the Moroccan

culture of today. A lasting influence like this would not have been possible without the previous strong relationship and understanding that Jewish and Amazigh tribes had from the very beginning of their encounter. Comingling and coexistence were the beginning of the Judeo-Amazigh relationship that resulted in one of the most lasting bases and most transformative influences on Moroccan values and tradition even as we know it today and which will be known as: The Judeo-Amazigh Cultural Substratum.

However, for Norman Berdichevisky, the presence of Jewish people in North Africa is recorded in historical chronicles even before 70 AD which makes the substratum older than thought:

“At its height in the 7th century BC (a thousand, three hundred years before the advent of Islam and the expansion of the Arabs out of the Arabian Peninsula and their conquests in North Africa including Morocco), a vast overseas Semitic civilization was established by the Phoenician states of Tyre and Sidon in alliance with ancient Israel. All the petty states mentioned in the Bible shared a common Semitic language and related alphabets that were later borrowed by the Greeks and Romans. At this time, the Arab people, their language and pre-Islamic and non-literate culture were confined to the Arabian Peninsula, a cultural backwater remote from both ancient Israel and Morocco. “

The advent of the cultural communion and harmony

Before the arrival of any monotheistic religion to Northern Africa, there were many different Amazigh tribes that lived in the area, which did not really have an official religion but rather a tribal way of life that bonded them as a people. These Amazigh tribes have existed and thrived in Northern Africa for over thirty centuries and, therefore, tribalism bonded these people as the reigning social ideology and as a successful system of governance.

[ads1]

This environment happened to be ideal and propitious for another group of tribal people who were fleeing their homeland in search for another welcoming environment where to live and prosper. After the destruction of the second temple in Palestine by the Romans, many of the surviving Jewish people decided to flee to Northern Africa where they found an already existing tribal way of life close to theirs. At the beginning, the Jewish people of Northern Africa inhabited rural areas like the mountainous areas of the north. They flourished in their surrounding because of the already existing tribal loyalties and respect for nature that is so prominent in both Amazigh and Jewish ways of life.

This transition to Northern Africa of the Jewish people, who represent a completely different religion and nation, could have resulted in conflict of some sort, yet they successfully settled down and flourished as a result of their strong sense of coexistence and comingling. Profession-wise, the Jewish people chose occupations of value and ended up becoming pillars of the community and some of its most trustworthy members.

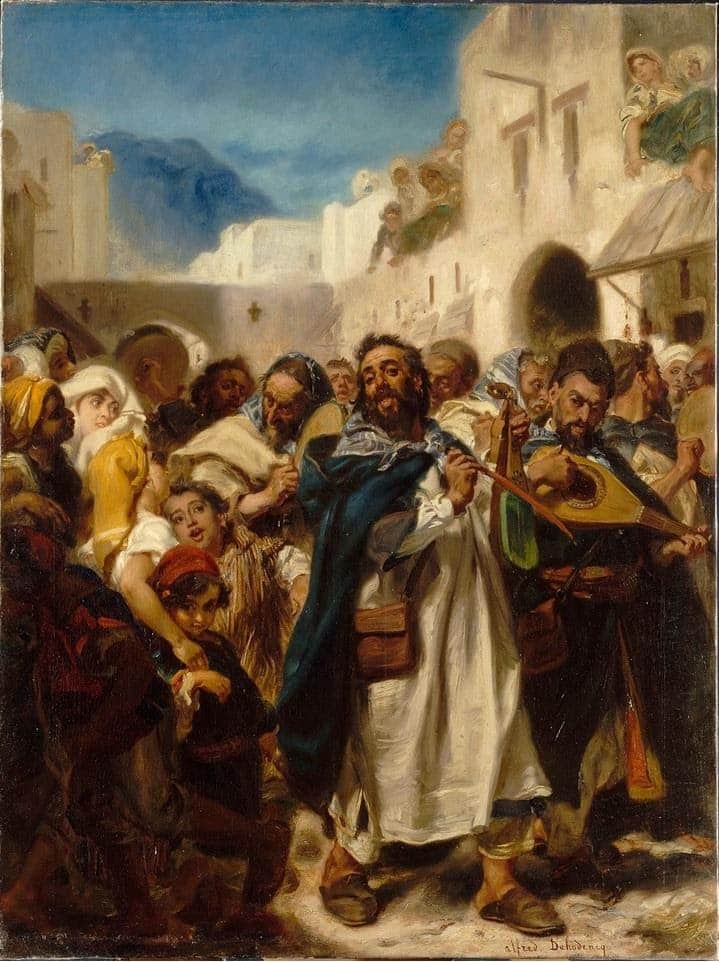

They became itinerant merchants ( going from place to sell various things like utensils and cosmetics), weighers (people who had the skills in the market to weigh as scales were not widely available and only those who were highly trusted by the state were chosen to do this), ironsmiths, goldsmiths, local bankers (people who would lend money with interest, they were so popular in this profession not only because they were trustworthy but also because they wouldn’t ask for the money back, if not available, but just increase the interest), and they were also caravan leaders (this was also a profession few were trusted and only Jews would bother to pay the tax of passage—in fact, the word for guide in Amazigh is azettat which refers to the piece of cloth he would carry on a long stick, visible from afar to indicate he had paid the tribal tax). These professions were extremely useful and community.

[ads1]

This transition and subsequent trust, in part, was inspired by the mutual understanding of a tribal way life as the two peoples functioned very similarly within their values, identity, and even traditions. Within the definition of tribalism there is an inherent loyalty that brings one to put community and family first in regards to responsibilities. The tribal system functions not only as a way of life but as a way of governance, as well. The first unit of both the Amazigh and Jewish tribal system is the family, the second unit being the extended family, the third being the clan and the forth unit being the tribe that banded together a limited number of clans (five clans in some cases.) In Jewish tradition, many tribes together become a nation whereas in Moroccan tradition many tribes together become a confederation or an alliance known as leff.

Not only were the tribal systems similar but the identities that held the tribes and their traditions together were, also, very close in regards to the fact that both social units being inherently democratic, possessed a strong work ethic, gave a large importance to women, and expressed their identity through tradition and language. Both Jewish and Amazigh tribes shared similar traditions of costumes, tattoos, jewelry and even rugs. These similarities led the way for a very positive and tight relationship and even to the conversion of some Amazigh tribes to Judaism.

Commonality morphed into togetherness

The strong base that resulted from this special relationship, originated from mutual respect and commonality between both Amazigh and Jewish tribes that morphed each other’s social systems into a culture of togetherness and harmony that is the basis of the reputed Moroccan way of life and philosophy of tolerance of today. Many things that are now viewed as traditional Moroccan culture, today, are originally traditional Jewish traditions like the worship of saints sâlihîn or Amazigh practices like the reverence of the Hand of Fatima known as khmîsa or khamsa.

Saint worship is even more unique because it is only found in North Africa, and is actually the unique contribution of both Amazigh and Jewish tribes to the religion of Islam in Northern Morocco as Judaism brought the practice and many of the most worshipped saints were Amazigh figures. This is one of the most lasting and profound effects of this special relationship on Moroccan Islam and on society as a whole. These two cultures continued to build each other into stronger presence in Moroccan identity even before the Islamization of North Africa.

[ads1]

This relationship provided not only a strong base but, also, a strong inspiration to keep and maintain tribal culture strong and flourishing. So much so that when Islam came to Northern Africa there was a very fierce resistance against this encroaching new force.

There are many Amazigh folktales that have emerged from this time but the most infamous is that of Princess al-Kâhina, also known as Dihya. Princess Al-Kâhina was an Amazigh princess of Jewish faith, yet claimed as a heroine by Amazigh peoples, Arabs, Jews, Christians, and even Muslims—she was also known to be a sorceress and she supposedly lived for 127 years and ruled for 65 years and had three sons. She was even documented by one of the most famous Arabic historians, Ibn Khaldun—lauding her as an “Amazigh Knight”—highlighting her courage, beauty and sense of tolerance.

She led a very fierce resistance against the forces of Islam and it took them about twenty years to defeat her. After the defeat of Princess al-Kâhina, though, those who were bringing Islam to Northern Africa realized they made a big mistake in how they were going about spreading Islam in the area and, thus, changed their ways in Islamizing the area in that they decided to accept local traditions and decided, also, to accept Judaism and tolerated it, therefore. Yet, still many pagan traditions survived in the mountains, till today, due to the obvious geographic obstacles, like the mystic music and dance of the world-famous Master Musicians of Jajouka in the Rif mountains.

Princess al-Kahina’s fame, also, alludes to the value placed on women by both Amazigh and Jewish tribes and her story represents the respect the women enjoyed, then. Throughout their common history it never ended up being Jewish against Amazigh tribes, yet they did band together as a confederacy under a Jewish- Amazigh Princess against the harsh Islamization of Morocco. So, the Jewish-Amazigh relationship and cultures both stood tall and continued to gain ground in their influence of Morocco and even North African Islam as a whole, for many centuries since.

For Haim Zafrani, this commonality gave birth to a rich oral literature, besides:

“Oral literature is an immense subject and difficult to define. It concerns folklore but also comes under the head of sociology, ethno-anthropology, and even history. Everything that has been said and then gathered up by collective memory belongs to this vast domain. Generally described as popular, it is constantly enriched by the work of scholars and very rapidly assimilates it. It is therefore legitimate to infer from this that popular literature preserves and transmits the creations of historic civilizations as well as the heritage of prehistoric cultures. However, its survival and transmission conform to certain rules and are subject to the operation of popular mentalities. The similarity of the mental structures of the Jewish and Muslim-Arab and Berber populations gave birth in the Maghreb to a literature and a folklore where the Jewish cultural substrata and the Arab-Berber heritage were united in an original creation.”

[ads1]

Cultural contributions

The Jewish people who were in the midst of this transition were able to take advantage of their situation of their easy adaptability, not only forwarding themselves in Moroccan culture but, also, making significant contributions to advance it as whole and leaving lasting legacies on both Judaism and Morocco. One of the reasons that the Jewish people and even the Amazigh people were able to flourish under Islam in Morocco was, also, because they were treated badly under the Romans, not to say they were literally emasculated and enslaved and the Arabs changed and abrogated this status in their approach to the Islamization of Morocco. All of the contributions that both Amazigh and Jewish people have made to Moroccan identity and society are the result of this strong foundational relationship.

[ads1]

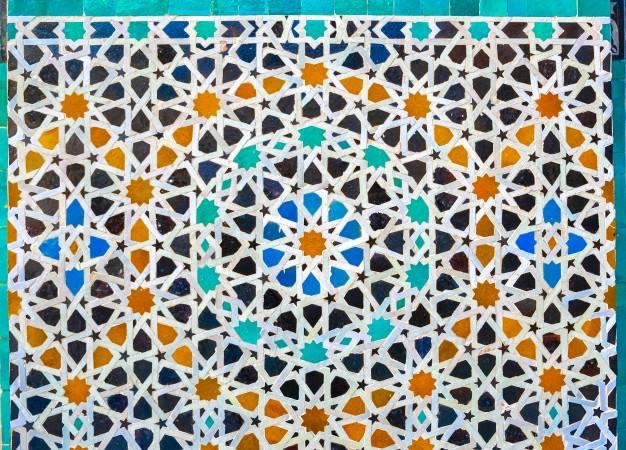

Jewish people contributed largely to what is known, today, as Moroccan culture by taking advantage of their situation and adapting to whatever cultural standards they were surrounded by and also enhancing the economy. Thinking about Moroccan art some of the first things that comes to mind is the zellige mosaic work found in architecture, as well as, in the motifs of the Amazigh rugs made in the mountains and sold all over the country. It actually happens that these famous rugs come from the Jewish tribal tradition—women would begin weaving the carpet upon the beginning of their pregnancy cycle and use themes that represent Kabbalistic motives and the life cycle which, also, happens to be the theme in which zellige tiles are created.

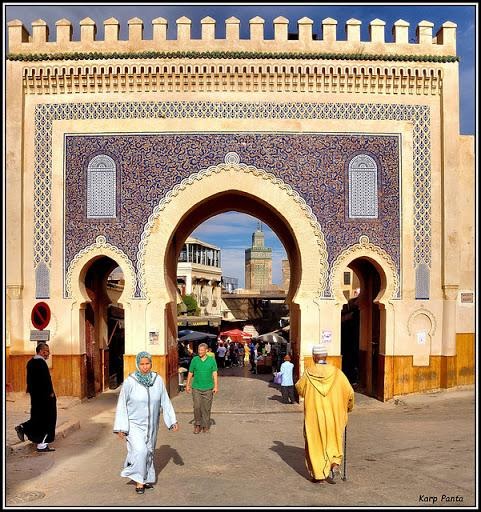

In Moroccan society, the Amazigh rug has lost its Jewish affiliation, yet is still used as a symbol of motherhood. The zellige tiles have, also, lost all of their affiliation with Judaism and have instead become a symbol of traditional Moroccan architecture. As well as this, Fez became one of the most artistic capitals of Morocco as it was known for its Jewish crafts guilds which, then, later, became Muslim as more and more people converted to Islam.

The Jews even developed their own idiom known as the Judeo-Amazigh/Berber spoken in southern Morocco whereas Judeo-Arabic was the language of the Jews of coastal towns. In this regard Joseph Chetrit argues:

“Despite the lack of walled quarters or distinct streets for the small Jewish populations, varieties of Judeo-Berber clearly developed in some rural and isolated communities of the High Atlas, among Jews who settled in the Ait Bu Ulli tribe near Demnat to the north of Marrakech, and among those who lived in the Tifnout region near the Ait Wawzgit (Ouaouzguite) tribes of the Moroccan Anti-Atlas range, at least during the 19th and the first half of the 20th centuries. For these small communities, Judeo-Berber was the principal and often the only language used by Jews, not merely in their interactions with neighboring Berber Muslims, but also within the Jewish family and in communal institutions. Many testimonies of Moroccan Jews who visited such communities in the 1930s and1940s, which were recorded in our fieldwork, as well as a Hebrew chronicle from1899–1902 (Chetrit 2007a: 230–232), attest to these monolingual uses. This linguistic situation lasted until the French Protectorate developed practical roads and paths between 1920–1940, which opened and strengthened the contacts between isolated rural Jews and urban Jews and progressively led monolingual speakers of Judeo-Berber to adopt Judeo-Arabic also and to become bilingual. “

After the second expulsion from Spain in 1492, about 50,000 more Jews came to Morocco. Because of their adaptability, during this time, Jewish scholars who learned Arabic in Andalusia resumed their admirable work of translating books from Greek into Arabic and into Hebrew—which in turn ended up kick-starting the European Renaissance. They, also, brought with them something that is now called “the culture of expulsion” which basically refers to the Spanish and Sephardic influence that these newcomers to Morocco had on music (Andalusian music known as tarab al-andalusî, a very popular classical music in addition to tarab cha’bî, pop music interpreted by the Botbol and Pinhas families of famous musicians of the 20th century), food, dress, and even economy.

[ads1]

Firstly, their impact on food from this period is still very prominent today-the strong use of garlic and fish and many of their salads like tomatoes and cucumber, and even one of the most popular dishes commonly called za’look which is made from roasted eggplant and red peppers and considered a real delicacy.

In addition, under the Saadi Dynasty Jewish people prospered economically thereby gaining the name of “the golden banking state” for Morocco. This was the result of the fact that the Saadi sultan gave Jewish people the monopoly of maritime trade and banking-and they took it in stride and kept the monopoly on the tea business until 1960. As for the sultan Sidi Mohammad ben Abdullah, he gave Jewish traders special privileges and so they moved to port cities like Tangier and Essouria (known, then, as Mogador) from whose ports they conducted international trade. Further, under the sultan Moulay Abd Abderrahmane, the Jews gained a whole monopoly of commerce with Europe and further developed the system of Tujjâr as-Sultân, which means the King’s Merchants. As a result of these two strategic business accomplishments, there are still many famous cities for either their current Jewish presence or their lasting Jewish legacies of coexistence among many other things such a famous food, dress or industry.

The French traveler Chenier attests to the great ingenuity of Moroccan Jews of the time of his visit to the Empire of Morocco (18th century):

“…the Jews have many advantages…: they better understand the spirit of trade; they act as agents and brokers, and they profit by their own cunning and by the ignorance of the Moors. In their commercial bargains many of them buy up the commodities of the country to sell again. Some have European correspondents; others are mechanics, such as goldsmiths, tailors, gunsmiths, millers, and masons. More industrious and artful, and better informed than the Moors, the Jews are employed by the emperor in receiving the customs, in coining money, and in all affairs and intercourse which the monarch has with the European merchants, as well as in all his negotiations with the various European governments.”

Moroccan Jewish legacy

Jewish people have managed, through either profession or innovation, to influence deeply the Moroccan identity in even its highest functions through politics, diplomacy, trade, scholarship or even farming. From the beginning they were able to take advantage of their reputation as trustworthy people to become the closest advisors to the king, even until today. After the Islamization of Morocco, they became the King’s “shadow cabinet” known as Hukamâ’ (wise people) listened to their military and diplomatic advice and this tradition was copycatted by Arab emirs in Spain during Muslim rule (711-1492).

Further, they were always chosen for positions of political power in many dynasties as a result of their intellect and trustworthiness. And using their economic success to their advantage, the Jewish people produced many famous diplomats that can be partly credited with Morocco’s success diplomatically then and today. In 1608, Samuel Pallache arrived in the Netherlands and signed the first pact of alliance between Morocco and a Christian country. Also, using their influential positions within the young republic of the United States, Isaac Nuves and Isaac Pinto were fully responsible for signing a friendship treaty with the Empire of Morocco in 1787.

[ads1]

Al-Qarawyyin University in Fes has, also, produced many great Jewish scholars who still contribute to today’s society with their lasting intellectual legacies. Rabbi Isaac Alfesi wrote the most famous early Talmudic commentaries after having studied at al- Qarawyyin University. Moshe Ben Maimoun, although born Jewish in Spain, came to Fez with his son as a guest of the Almohad Sultan and taught medicine and comparative religion at al-Qarawyyin University, at the same time producing some of his best theological and scientific work.

Moshe Ben Maimoun is better known as Maimonides and he is now known to rectify Aristotelian beliefs. As to what concerns Jewish theology, he is well known for his thirteen principles in his commentary of the Mishnah which he wrote mainly in Arabic. Maimonides and his work are largely recognized as symbols of the reconciliation of Muslim and Jewish scholarship and cultures. In fact, if we take the combined works of the many great minds and diplomats of this time and even today, there is no way to deny the unique and diverse quality knowledge, experience and expertise brought by Jewish peoples’ migration to Morocco under the Roman Empire and invigorating its civilization and way of life.

Moroccan proverbial tolerance

While the Jewish community of Morocco has mostly vanished in the 70s of the last century, it has, undeniably, left a positive legacy for what we now know of Moroccan identity and culture. This is evident in many aspects of Morocco’s political and cultural persona today like Morocco’s notorious tolerance to many different religions let alone different kinds of Islam and even uniqueness and exception in the Middle East and North Africa region. Morocco has always maintained a good relationship with its cultural bases-being both the Amazigh and Jewish people.

The Amazigh nationalist wave happened all across Northern Africa, along with other protests for government reform mainly the Arab Spring and King Mohammed VI took the initiative from those who were demanding reform and promoted a new constitution to Morocco that recognized the Amazigh language and culture as a core component of Moroccan identity. King Mohammed VI, also, recognized many Jewish contributions to this identity as a part of the 2011 constitution, as well, and restored one of the ancient synagogues in Fez.

Even during World War II, Morocco was known to be a friendly place for Jewish people to flee to. After the creation of Israel, the Jewish population of Morocco decreased dramatically yet their presence and legacies and the warm reception Moroccans have to them has never left. It lives on through Morocco’s unique and multifaceted identity, Amazigh political activism, and even constitutional reforms made from a tolerant King.

Judaism in today’s Morocco

The coastal town of Safi, home to the shrine of Rabbi Abraham Ben Zmirro, remains a pilgrimage site for Jews from around the world. The western Moroccan city of Essaouira, home to the tomb of Rabbi Pinto, a venerated rabbinical judge who died in 1845, also attracts hundreds of Jews every year for a four-day celebration of his legacy.

Though many Jews immigrated to Israel, France, Canada, and elsewhere beginning in the 1940s:

“The Moroccan government, for its part, has embraced those who remained, and its support of the community has been held up as a symbol of Arab moderation and tolerance” (The Forward)

There are an estimated 3000 Jews currently living in Morocco, and there are synagogues in Casablanca, Essaouira, Marrakesh, and Fez, with over 15 active synagogues in Casablanca alone.

Today, Serge Berdugo and Andre Azoulay, prominent members of Morocco’s Jewish community, serve as Ambassador at Large and Counselor to King Mohammed VI, respectively. Ambassador Berdugo is also the elected President of the World Organization of Moroccan Jewry. In April 2016, Casablanca hosted the country’s first Jewish film festival. Nearly 500 people attended three movie screenings on subjects relating to the Moroccan Jewish diaspora.

[ads1]

Morocco is engaged in a large-scale project to refurbish synagogues and other Jewish monuments to preserve the unique and historic aspects of Moroccan culture. Morocco’s “Houses of Life” project, launched in April 2010, restored 167 Jewish cemeteries across the country, installing 159 new doors, building nearly 140,000 feet of fencing, and repairing 12,600 graves. King Mohammed VI has said that this project,

“is a testimony to the richness and diversity of the Kingdom of Morocco’s spiritual heritage. Blending harmoniously with the other components of our identity, the Jewish legacy, with its rituals and specific features, has been an intrinsic part of our country’s heritage for more than three thousand years. As is enshrined in the Kingdom’s new Constitution, the Hebrew heritage is indeed one of the time-honored components of our national identity.”

In February 2013, the 17th century Slat al Fassayine Synagogue in Fez reopened after two years of restoration. In a message for the inauguration ceremony, King Mohammed VI said,

“I am committed to defending the faith and the community of believers, and to fulfilling my mission with respect to upholding freedom of religion for all believers in the revealed religions, including Judaism, whose followers are loyal citizens for whom I deeply care… The Moroccan people’s cultural traditions, which are steeped in history, are rooted in our citizens’ abiding commitment to the principles of coexistence, tolerance and harmony between the various components of the nation.”

In April 2013, the Casablanca-based Museum of Moroccan Judaism, the only institution of its kind in the Arab world, was opened to the public. The museum displays photos of synagogues from across the kingdom, Torah scrolls and Chanukah lamps, gold embroidered caftans, jewels, ancient rugs, and other objects of the Jewish-Moroccan cultural heritage. King Mohammed VI has, also, funded the preservation of Jewish burial sites in Cape Verde, once home to a vibrant Moroccan Jewish community.

Adopted by referendum in 2011, the Moroccan Constitution states that the country’s unity “is forged by the convergence of its Arab-Islamic, Berber and Saharan-Hassanic components, nourished and enriched by its African, Andalusian, Hebraic and Mediterranean influences,” and emphasizes Morocco’s attachment “to the values of openness, of moderation, of tolerance and of dialogue for mutual understanding between all the cultures and the civilizations of the world.”

In a March 2009 speech launching the Aladdin Project for intercultural dialogue, King Mohammed VI called the Holocaust “one of the most tragic chapters of modern history.” This was the first time an Arab state had taken such a clear stance on the Holocaust. In a message on the occasion of the International Day in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust held at the United Nations on January 27, 2010, Morocco’s King Mohammed VI said that remembering the Holocaust,

“strongly imposes ethical, moral and political standards which will, tomorrow, be the true guarantors of this peace – based on equally-shared justice and dignity – and for which most Palestinians and Israelis yearn.”

[ads1]

Conclusion

When looking at culture from an anthropological or even sociological standpoint, there is a very strong trend of the influence that other cultures have on each other from many sources—be it globalization, technology, conflict, migration or religion. So, in the face of all of this influence, what makes a culture unique to any certain place? It is the way in which a group of people or a nation uses the influences that may come from religion, war or invasion to make traditions and an identity-almost like a personality-that is indeed specific to the place and the people.

This is what fascinates, attracts, and even confuses about Morocco. It is a place that has managed to do all of this and is still growing in many ways. The tolerance that has resulted from such a diverse past is evident in the paradox of Moroccan society today—the most unique Muslim country known to be a safe haven to the Jewish people. Even further, Moroccan Jews are the witnesses of a possible peaceful and beautiful coexistence between Arabs and Jews as evidenced by the depth of Moroccan culture today. This depth, beauty, and tolerance of Moroccan society is a sure one because it is a learned human experience.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Amazigh World News’ editorial views.